Beryl Bainbridge: Author, Artist

British author Beryl Bainbridge was not a reserved figure. She was many things - dramatic, beautiful, brilliant, complex - but she was not reserved.

Bainbridge often told interviewers that she took the plots and characters of her many acclaimed novels straight from real life, whether her own or historical. Perhaps because she was so forthcoming about this, there has always been speculation about where her personal history stopped and fiction started. Did she really do THAT and think THAT? But if one is able to overcome the urge to account for things in ordered columns of fact and fiction, and instead let the whole of Bainbridge’s output wash over you in one great sweep of Beryl-ness, it becomes very clear that she told us exactly who she was and how she lived, over and over again. Whether in fiction or prose, on film or canvas, Bainbridge had an unmistakable point of view. She was always Beryl, through and through.

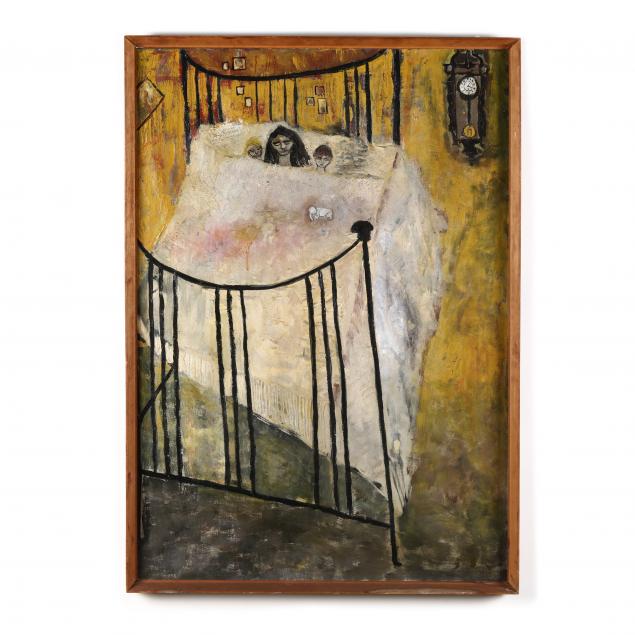

In our New Year’s Day Auction we offered an original painting by Bainbridge, The Bed, in which Bainbridge painted herself asleep with her three children in the same big brass bed that viewers can spy in the several interviews and documentaries of her filmed inside her Camden, London, townhouse. She painted often throughout her life, but only a very few of her paintings have ever come to the secondary market. And so we take the occasion of the rare surfacing of one of her paintings to revisit some of the aspects of Bainbridge’s life that encapsulate that singular Beryl Bainbridge way of being.

Beryl Bainbridge (British, 1932-2010), The Bed

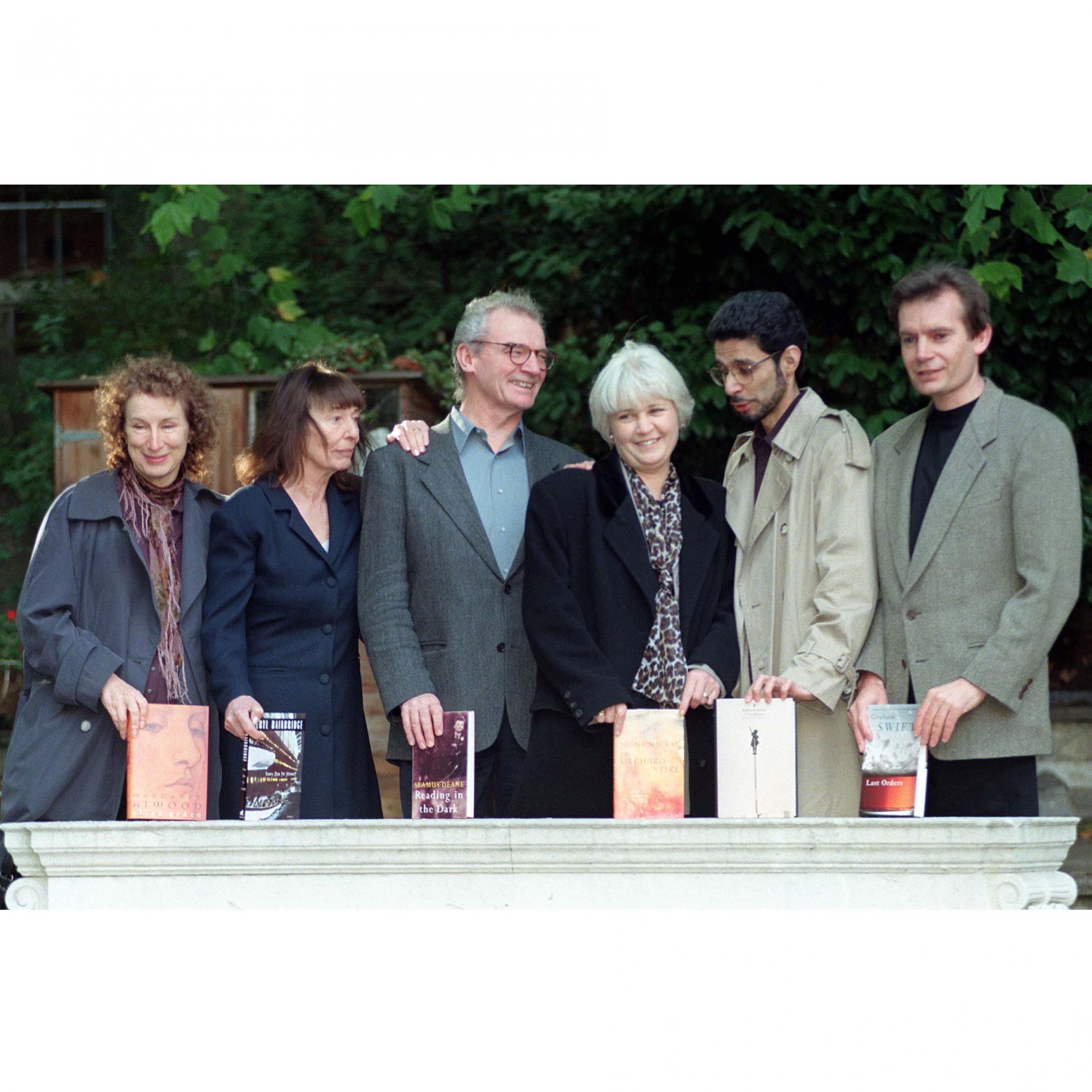

Bainbridge with other authors shortlisted for the 1996 Booker Prize. From left: Margaret Atwood, Beryl Bainbridge, Seamus Deane, Shena Mackay, Rohinton Mistry, and Graham Swift

She was the “Booker Bridesmaid”

You know, always a bridesmaid, never a bride. Bainbridge was nominated five times for the Man Booker prize, England’s highest literary honor. Only three authors have been nominated more often, each six times. But while she was given a number of prestigious honors for her writing, including a Damehood and the Whitbread Prize three times, Bainbridge never took home the Booker during her lifetime.

It wasn’t until she died that the Man Booker organization corrected the oversight, and created a special “Best of Beryl” Booker award. The public was allowed to pick which of her nominated books to give the award to - they chose Master Georgie, an historical fiction about the Crimean war. Mark Knopfler, evidently a fan, included a song on his 2015 solo album Tracker titled “Beryl” with the lyric “Beryl, every time they’d overlook her/When they gave her a Booker/She was dead in her grave/After all she gave.” Asked about the disappointment of being so often nominated and never selected for the Booker, Bainbridge once replied “The prize I value most was given to me 60 years ago. I was named the girl with the cleanest fingernails.”

She painted as a release from writing

There were few artistic outlets that Bainbridge didn’t try on for size. Her oldest daughter, Jojo Davies, expressed the angst of growing up in Bainbridge’s shadow: any artistic avenue her children wanted to explore, their mother had gone before them, with talent and flair. While Bainbridge is of course best remembered for her volumes of writing, her first calling was as an actress. Bainbridge was born and raised in Liverpool, and as a young woman she began acting at a local theater. There she met the artist Austin Davies, who was painting scenery for the playhouse. They were married in 1954. Bainbridge took up painting as well, and sold her artwork in the couple’s early married years to make ends meet. After she and Davies divorced, Bainbridge once again returned to acting. But when she became romantically involved with the Scottish writer Alan Sharp in the early 60s, Bainbridge turned to writing to earn a living and never looked back. She would still paint on occasion, often when she finished a novel. She described painting as what she did for fun, whereas writing was work. Her paintings were often a fantastic mash-up of characters from her books, her life, and history. Napoleon figures prominently. During one phase, figures in her paintings - Napoleonic or otherwise - were almost always naked, save for perhaps a jaunty hat.

After Bainbridge’s death in 2010, The Museum of Liverpool and King’s College London mounted exhibitions of her paintings. The art was treated as a bit of a posthumous surprise to the public who had known her for so long as a writer. Most of the paintings in the exhibits were ones owned by Bainbridge’s children, the whereabouts of her other works being unknown. One newspaper, in the lead up to the shows, ran an article asking readers to check if they might have a Beryl Bainbridge painting hanging on their wall without realizing it. Now, of course, critics love to lay out her art and her writing to compare. Was she actually a better artist than a writer? Suffice to say, both reflect her wildly imaginative creativity that somehow still remained firmly tethered to the ground.

After Bainbridge’s death in 2010, The Museum of Liverpool and King’s College London mounted exhibitions of her paintings. The art was treated as a bit of a posthumous surprise to the public who had known her for so long as a writer. Most of the paintings in the exhibits were ones owned by Bainbridge’s children, the whereabouts of her other works being unknown. One newspaper, in the lead up to the shows, ran an article asking readers to check if they might have a Beryl Bainbridge painting hanging on their wall without realizing it. Now, of course, critics love to lay out her art and her writing to compare. Was she actually a better artist than a writer? Suffice to say, both reflect her wildly imaginative creativity that somehow still remained firmly tethered to the ground.

Her romantic life had enough plot twists for a library’s worth of books

It’s no wonder that Bainbridge found plenty of fodder for fiction in her own experiences. Each one of her relationships would require most of us many hours on a therapist’s couch to recover. First, when she was 15, was the German WWII former prisoner who was in Liverpool awaiting repatriation to Germany. When he was finally sent home, he and Bainbridge carried on a romance through letters while trying to get him permission to return to England, which was at last denied. A year later, Bainbridge met Davies, her first husband, with whom she had her first two children. When they divorced after Davies’ many infidelities, he bought her the house in Camden in which she would live for forty years, and moved himself into the basement flat, where he stayed even after he had remarried. In the meantime, Bainbridge met Alan Sharp, who introduced himself to her by telling her that he was going to be on television that evening to promote his new movie, and would she watch? She replied that she didn’t have a television set. Not to worry, he had one sent to her house that same afternoon. The rest, as they say, is history. Or fiction, if you’re Bainbridge. The whole situation appears as a plot point in her later book Sweet William. Bainbridge and Sharp were together long enough for her to have another child, their daughter Rudi. When Rudi was small, by Bainbridge’s account, Sharp told her he was going to get a book out of the car and never came back.

But Bainbridge was far from spoiled for love. In the latter half of her life she carried on a decades-long affair with her publisher, Colin Haycraft of Duckworth Ltd., despite the fact that it was Haycraft’s wife Anna who, as Duckworth’s fiction editor, befriended Bainbridge and brought her to the publishing house. This was not the only romantic partner the two women shared - Anna also had a devastating relationship with Austin Davies just before he married Bainbridge. Many of the small details of these and other affairs made it into the fabric of Bainbridge’s books and paintings.

But Bainbridge was far from spoiled for love. In the latter half of her life she carried on a decades-long affair with her publisher, Colin Haycraft of Duckworth Ltd., despite the fact that it was Haycraft’s wife Anna who, as Duckworth’s fiction editor, befriended Bainbridge and brought her to the publishing house. This was not the only romantic partner the two women shared - Anna also had a devastating relationship with Austin Davies just before he married Bainbridge. Many of the small details of these and other affairs made it into the fabric of Bainbridge’s books and paintings.

Her grandson made a documentary about what she predicted would be the last year of her life (spoiler: it wasn’t).

Beryl Bainbridge was convinced she would die at 71. Her mother died at 71, her father died at 71, a handful of other relatives all died at 71. And so, upon her 71st birthday Bainbridge tasked her oldest grandson, Charlie Russell, with documenting her last year of life. The film, which was shown on BBC Four and is available on YouTube, is a wonderful opportunity to hear Bainbridge tell firsthand the stories that she incorporated into her work. The pair visit her childhood home in Liverpool, so clearly the scene of the opening of her book A Quiet Life. They walk down the roads where she met the German soldier, and pick out the townhouse where she lived with Austin Davies. There, she tells us, John Lennon and Stuart Sutcliff, students of Davies’ at the Liverpool School of Art, came to play on the night of her divorce, and made so much noise that the neighbors called the police. About two thirds of the way through the film, Charlie and Beryl visit the graves of Bainbridge’s parents and discover that they both actually died at 70.

The entire film is punctuated by Bainbridge’s rasp and cough, harbingers of the lung cancer (after a lifetime of smoking scores of cigarettes a day) that would eventually be the cause of her death in 2010 at 77 years old. But when the documentary concludes, we are at Bainbridge’s 72nd birthday celebration. Having discovered that she has already outlived her parents, she deigns to take on another year. Her grandson asks her what she’ll do when she finishes the book with which she has been struggling throughout the filming. I’ll write another, she says. And then another. But maybe not another after that. Maybe I’ll do some painting instead.