Five Things: The Decorous Revolution of Women in American Art Pottery

Not all revolutions come with rally cries and drum beats. Some, like the rise of American women ceramicists at the turn of the century, are more quietly radical, but they bend the arc of equality nonetheless.

To illuminate the history behind the American art pottery in our July Estate Auction, we take look at five interesting facts about the late 19th and early 20th century women who found themselves a vocation by way of a crafty hobby.

1. A Respectable Pastime

From Lett's Household Magazine in 1884:

In the household, china-painting affords amusement for the girls in the family during the hours their brothers and father leave for business, and return in the evening. To many such ladies, who have nothing better to do than novel reading, this method of filling their time will be esteemed a great boon. Doubly so, since their work may be used either as decorations to the wall surface, if it be plaques they paint, or else disposed of at a profit to themselves to increase their pin-money, or may be given to some bazaar for charitable purposes.

As unpalatable as it is, it's possible that the thick condescension in this passage is precisely the reason that non-working class 19th century women managed to turn porcelain painting into a viable business. Artistry hidden in decoration, the porcelain-painting craze of the turn of the century gave women an outlet for otherwise stifled creative energy. And then, with "brothers and father" lulled into complacency by the non-threatening nature of their work, they slowly began to sell their art, blowing "pin money" out of the water.

In the household, china-painting affords amusement for the girls in the family during the hours their brothers and father leave for business, and return in the evening. To many such ladies, who have nothing better to do than novel reading, this method of filling their time will be esteemed a great boon. Doubly so, since their work may be used either as decorations to the wall surface, if it be plaques they paint, or else disposed of at a profit to themselves to increase their pin-money, or may be given to some bazaar for charitable purposes.

As unpalatable as it is, it's possible that the thick condescension in this passage is precisely the reason that non-working class 19th century women managed to turn porcelain painting into a viable business. Artistry hidden in decoration, the porcelain-painting craze of the turn of the century gave women an outlet for otherwise stifled creative energy. And then, with "brothers and father" lulled into complacency by the non-threatening nature of their work, they slowly began to sell their art, blowing "pin money" out of the water.

American Art Pottery in the July Estate Auction

2. It Started with a Tea Party

In 1875, a group of well-heeled Cincinnati women painted tea cups and saucers to be sold at the Centennial Tea Party, a fundraiser to benefit the Cincinnati exhibit at the 1876 Philadelphia Centennial Exposition. The event was hugely successful, and much of the porcelain sold at the Tea Party was then exhibited, along with other pieces, at The Women's Pavilion at the Centennial Exposition.

3. The First Woman-Owned American Manufacturer

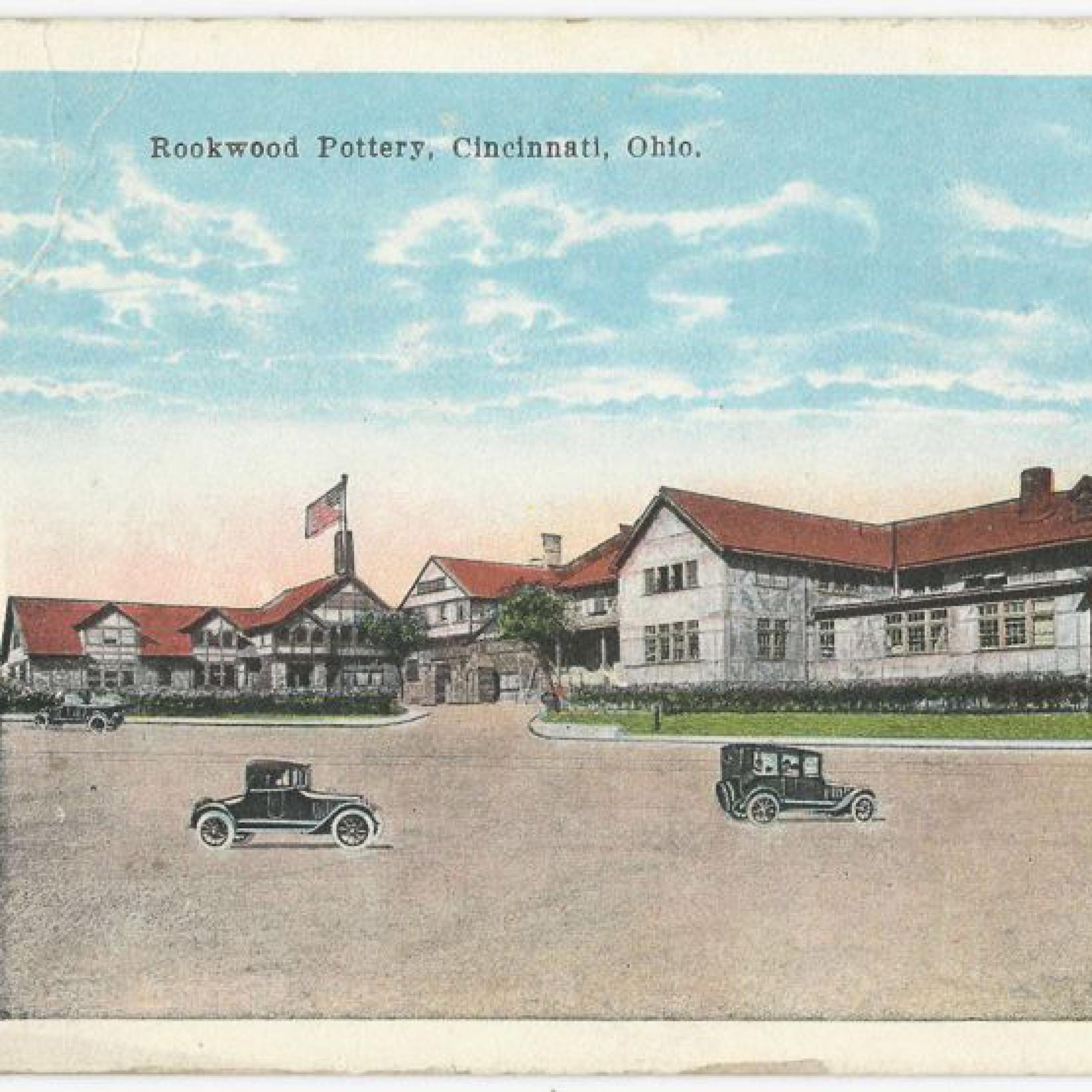

After the success of The Centennial Tea Party, and her exposure to Japanese art at the Exposition, one Cincinnati porcelain painter, Maria Longworth Nichols, had a kiln built at one of the local pottery shops where she bought her blanks for painting. Just a year later, she opened her own shop, Rookwood Pottery. Longworth Nichols gained international recognition for the ceramics she oversaw at Rookwood, but after her first husband passed away and she remarried a politician and moved to Washington D.C., she sold Rookwood to her business manager. But she continued to make art as Maria Longworth Nichols Storer, and Rookwood remains in operation to this day.

Rookwood Pottery

Maria Longworth Nichols Storer

4. The Rivalry

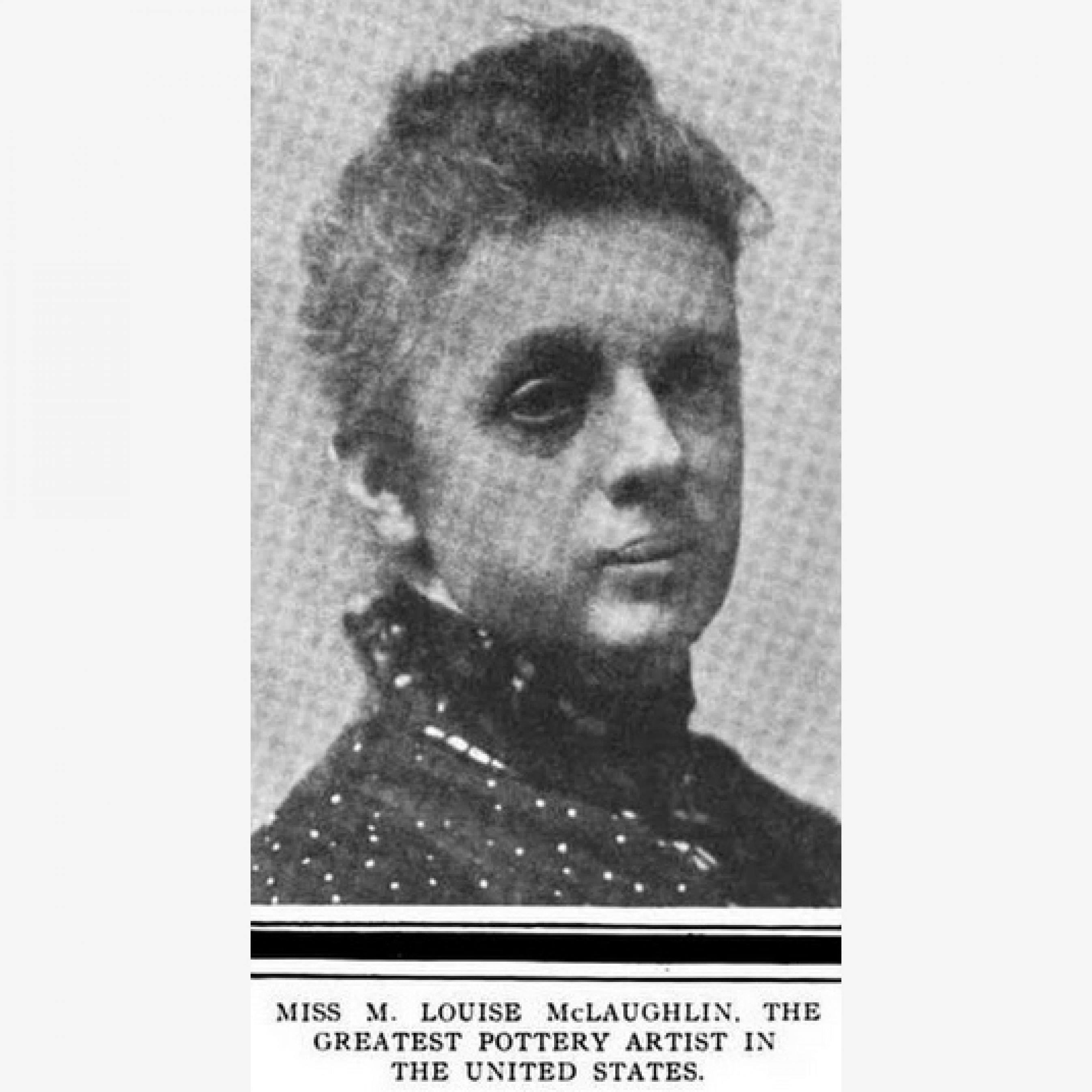

Longworth Nichols wasn't the only art pottery name that emerged from The Centennial Tea Party. In fact, she sold only the second highest number of pieces at the Tea Party. Mary Louise McLaughlin, who would become Nichols' biggest rival, sold the most. And forever after, there was a competitive relationship between the two women, which may well have helped to spur them forward.

A portrait of M. Louise McLaughlin in a 19th century publication, with caption tailor-made to enflame her rival

In 1877, M. Louise McLaughlin published a book on china painting. In 1878, Longworth Nichols' husband published a book on pottery, with illustrations by his wife. In 1879, McLaughlin started the Cincinnati Pottery Club, the first women's ceramics decorating club in the United States. Longworth Nichols claimed not to have received an invitation, and refused to join - a major snub in terms of Cincinnati society.

McLaughlin's Pottery Club fired, showed, and sold their work at the Dallas Pottery, where Longworth Nichols also had a studio. In 1880, Longworth Nichols opened Rookwood, and hired away most of Dallas Pottery's skilled workers. When the owner of Dallas Pottery died in 1882 and the pottery finally closed, The Cincinnati Pottery Club was forced to rent space from Rookwood. But in 1883, Longworth Nichols evicted them, for reasons lost to history. The final battle between the women came in 1893, when, in a catalog for The World's Columbia Exposition, another potter claimed that McLaughlin was responsible for introducing the underglaze method of decorating ceramics to the United States. Longworth Nichols Storer took umbrage. She and the Rookwood manager demanded that the catalogs be reprinted, without the credit to McLaughlin, and offered to pay for the reprinting.

The Newcomb College Pottery salesroom

5. The Southern Outpost

Newcomb College Pottery, one of the other commercial success stories of women in American art pottery, operated on a slightly different model from its Northern cousins. Started as part of Newcomb College, the women's arm of Tulane University (and the first women's ancillary of a major men's university in the country), the Newcomb College Pottery became a for-profit business as its pottery became more and more popular. What started as an acceptable mode of arts education for women quickly morphed into a way for women to pursue a paid career in the arts. The for-profit Newcomb Pottery closed only as opportunities for artists outside the college model expanded.

Featured lots of American art pottery from the July Estate Auction, including period Rookwood and Newcomb College pieces, are below.

The July Estate Auction

Thursday, July 15th

10:00am (EDT)

The July Estate Auction

Thursday, July 15th

10:00am (EDT)