In every occupation, there are unsung heroes of feminism who led the way for the representation of women. Hester Bateman, whose silver workshop was hugely successful in late 18th century London, when very few women had their own silver hallmarks, is certainly one of those pioneers.

Like most women working in silver at the time, Hester Bateman was brought into the workshop by her husband - women were only allowed to apprentice with silversmiths in the 18th century because the demand for silver had increased so dramatically, and their husbands, fathers, and brothers needed the help. Male silversmiths were fined if they employed women who were not closely related to them, and all of the work that women silversmiths produced carried their male relatives' hallmark. But, as was the case with Hester, once a woman was widowed, she was allowed to register her own hallmark. When Hester Bateman's husband died in 1760, he left her his tools in his will, and she started to produce pieces carrying her own hallmark.

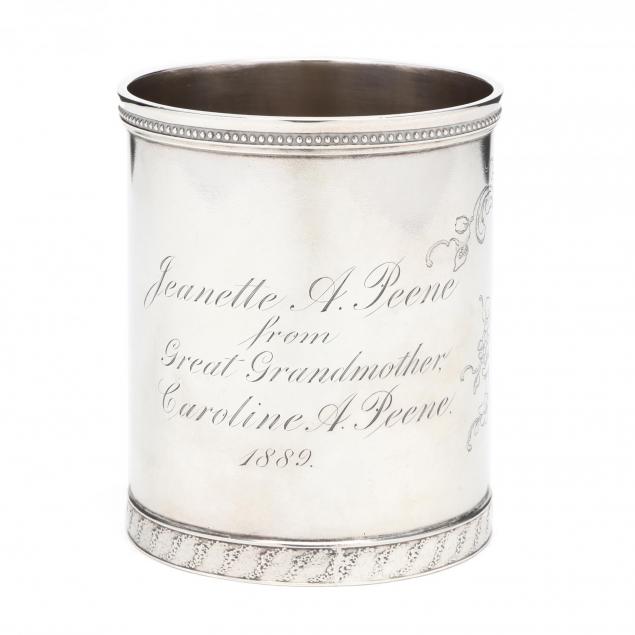

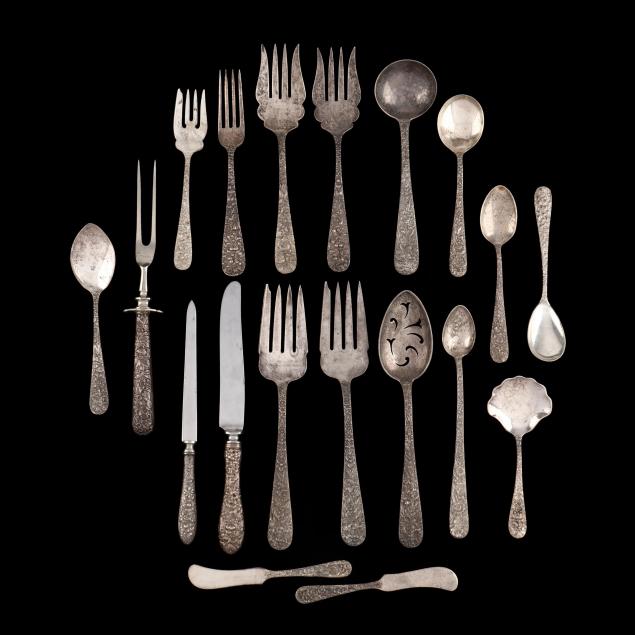

Bateman knew her market demographic. She made household items like tea and coffee services, flatware, and cruets, at prices the burgeoning middle class could afford. She harnessed modern technologies like using machines to punch out patterns, and applied those techniques to making the neo-classical designs that aspirational homemakers wanted to display. Bateman worked to expand her business with two of her six children, Jonathan and Peter, and her daughter-in-law Ann. After Bateman retired in 1790, her family registered their own trademarks and ran a successful operation well into the 19th century.

George III Silver Teapot, Mark of Hester Bateman

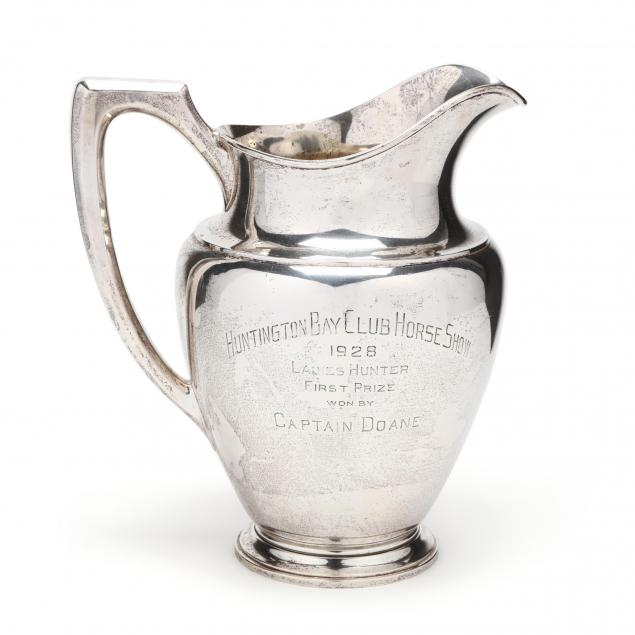

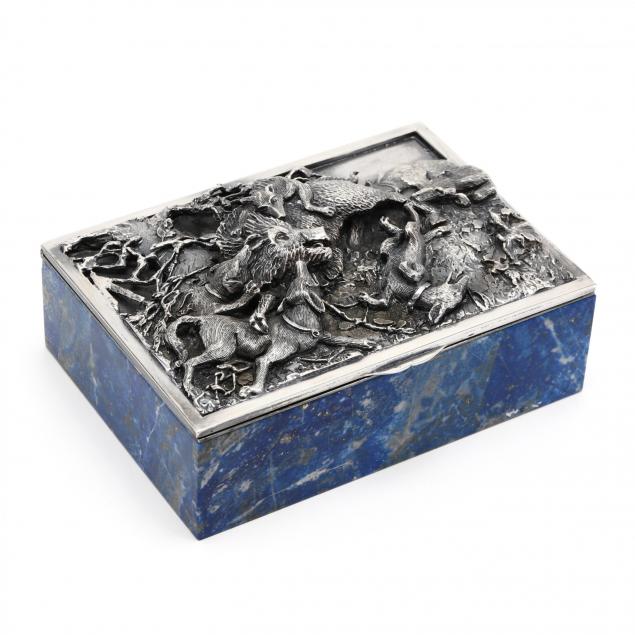

View the full selection of silver in our November 22nd Online-Only Auction below.

View the full selection of silver in our November 22nd Online-Only Auction below.