These days it's all about the edges vs. the center. They push and pull at one another as if they aren’t part of the same whole. But two of the artists whose work was offered in our Signature Spring Auction - J.C. Leyendecker and Charles Addams - remind us that there’s really no line between the fringe and the middle. Culture flows back and forth between them in a seamless exchange. Here we look at how Addams and Leyendecker managed to live alternative lifestyles in plain sight, all while crafting the touchstones of American life.

Charles Addams

The Hearsts, the Rockefellers, the Mellons, the Kennedys, the Addams. These are the families that shaped America. The Addams, of course, in a creepier, kookier way than the rest.

Given his fictional family legacy, Addams Family creator Charles Addams’ early life was shockingly banal. He famously told an interviewer “I know it would be more interesting, perhaps, if I had a ghastly childhood—chained to an iron beam and thrown a can of Alpo every day, but I’m one of those strange people who actually had a happy childhood.” The quote reveals Addams’ predilection for turning the notions of “strange” and “normal” on their heads. The only child of a happily married piano salesman, Addams spent his childhood in Westfield, Connecticut honing a wicked sense of humor - pranking his grandmother by jumping out of the dumbwaiter, sneaking into creepy abandoned houses, drawing Kaiser Wilhelm II being boiled in oil and the like. You know, as healthy, happy boys do.

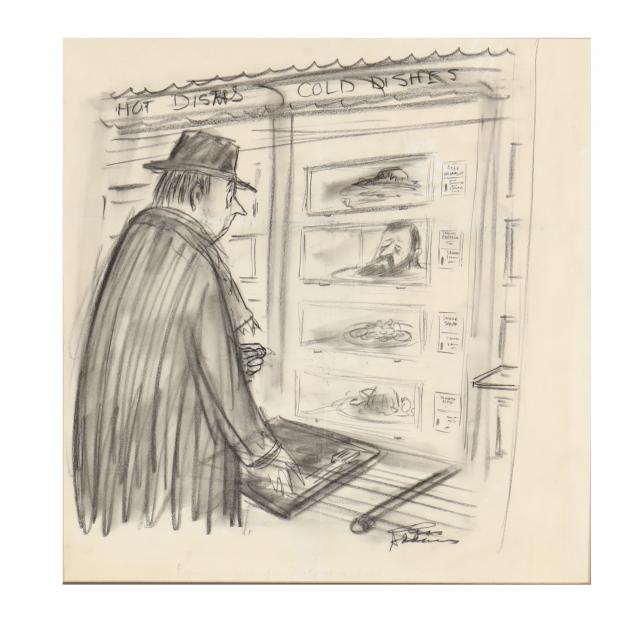

After graduating from art school, Addams parlayed his first job retouching the blood out of crime scene photos for the magazine True Detective into a regular gig at the newly launched New Yorker magazine. It was there that Addams’ talent for combining the mundane and the macabre in hilariously chilling cartoons made him a household name. Morticia Addams made her first appearance in a 1938 cartoon in which a shiny vacuum cleaner salesman regales her with the benefits of his product for any “well-appointed home” while standing in the shadow of her lumbering, undead-looking butler in a cobweb-adorned foyer.

Given his fictional family legacy, Addams Family creator Charles Addams’ early life was shockingly banal. He famously told an interviewer “I know it would be more interesting, perhaps, if I had a ghastly childhood—chained to an iron beam and thrown a can of Alpo every day, but I’m one of those strange people who actually had a happy childhood.” The quote reveals Addams’ predilection for turning the notions of “strange” and “normal” on their heads. The only child of a happily married piano salesman, Addams spent his childhood in Westfield, Connecticut honing a wicked sense of humor - pranking his grandmother by jumping out of the dumbwaiter, sneaking into creepy abandoned houses, drawing Kaiser Wilhelm II being boiled in oil and the like. You know, as healthy, happy boys do.

After graduating from art school, Addams parlayed his first job retouching the blood out of crime scene photos for the magazine True Detective into a regular gig at the newly launched New Yorker magazine. It was there that Addams’ talent for combining the mundane and the macabre in hilariously chilling cartoons made him a household name. Morticia Addams made her first appearance in a 1938 cartoon in which a shiny vacuum cleaner salesman regales her with the benefits of his product for any “well-appointed home” while standing in the shadow of her lumbering, undead-looking butler in a cobweb-adorned foyer.

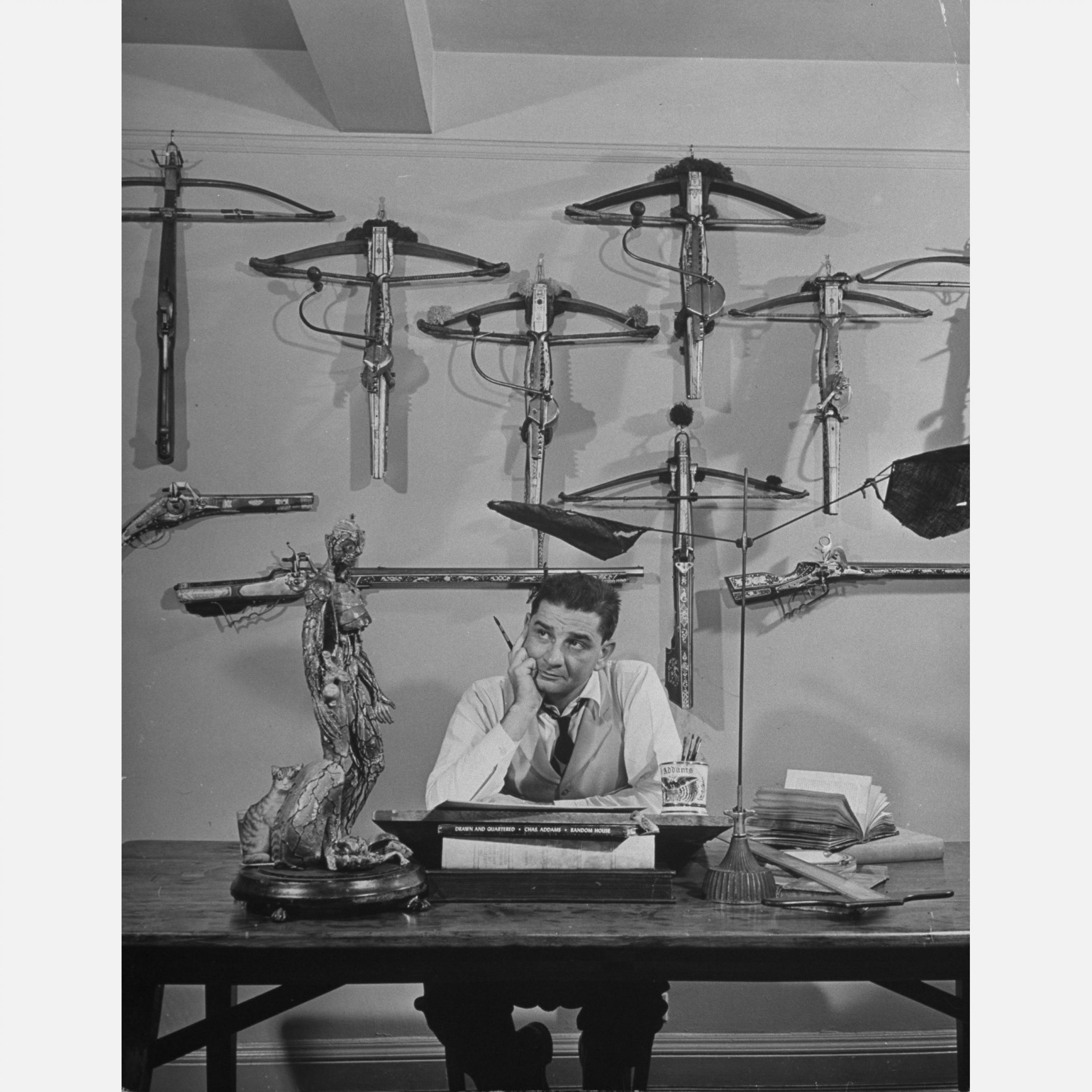

Charles Addams at home

Charles Addams embraced the same unflinching synthesis of the weird and the conventional in his personal life that he portrayed in his cartoons. He married three times, twice to women named Barbara who looked a lot like Morticia Addams, and once in the pet cemetery in which he would later be buried. In between wives, he courted Greta Garbo, Jane Fontaine, and Jackie Kennedy. He used an embalming table as a coffee table, a child’s tombstone as a spot to put his cocktail, and he collected crossbows. He was wildly famous, with fans like Alfred Hitchcock and Ray Bradbury, but Addams’ success was ultimately more cult than commercial.

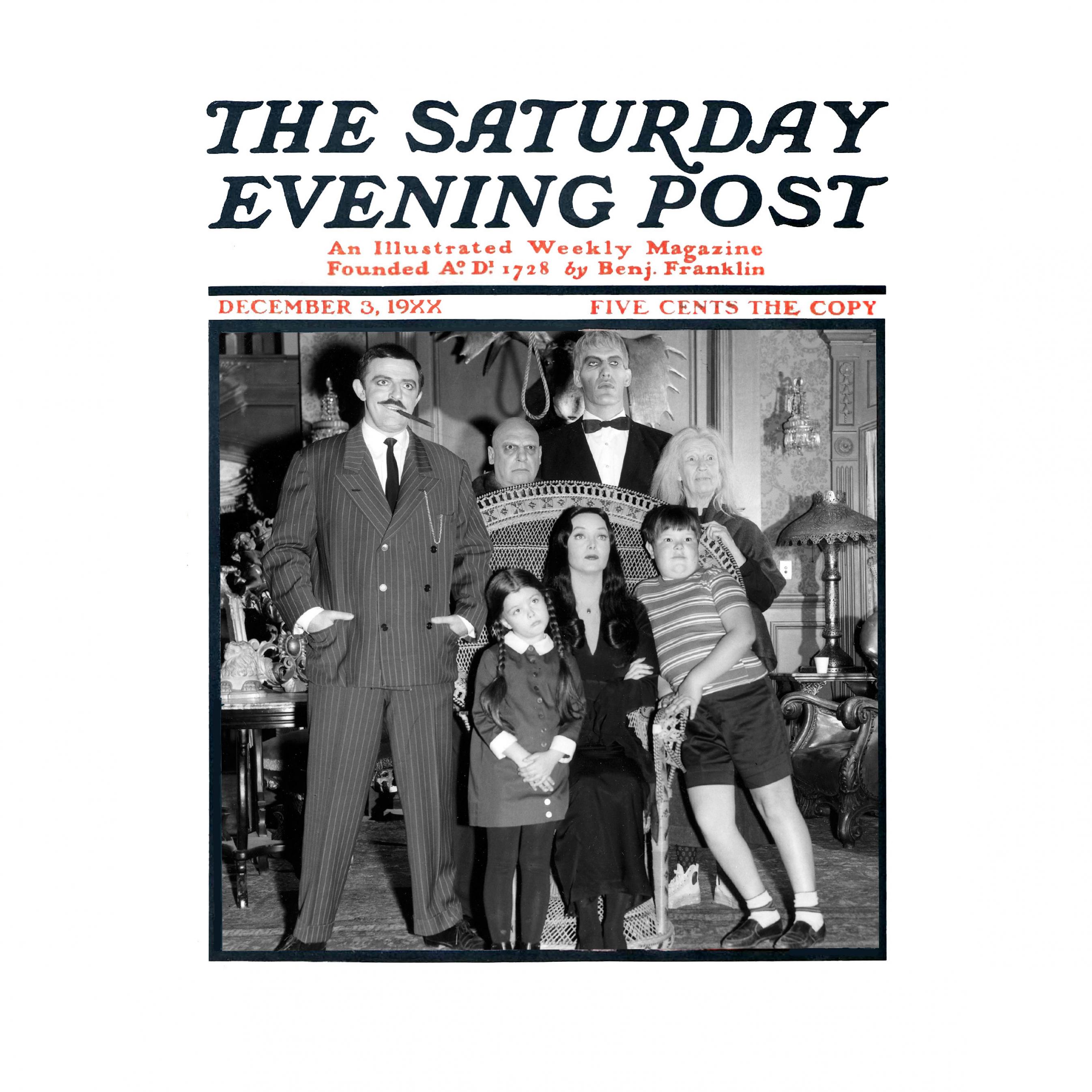

The endurance of the Addams family in the American zeitgeist is doubtless due to exactly the incongruity that makes them such unlikely heroes. Charles Addams and the creepy yet loving Addams Family showed mid-century America, straining against the confines of its apple-cheeked normality, that it was possible to be weird AND good, that being different didn’t have to mean being unhappy, unless being unhappy is what makes you happy. And if that isn’t a lesson for the ages, call us Uncle Fester.

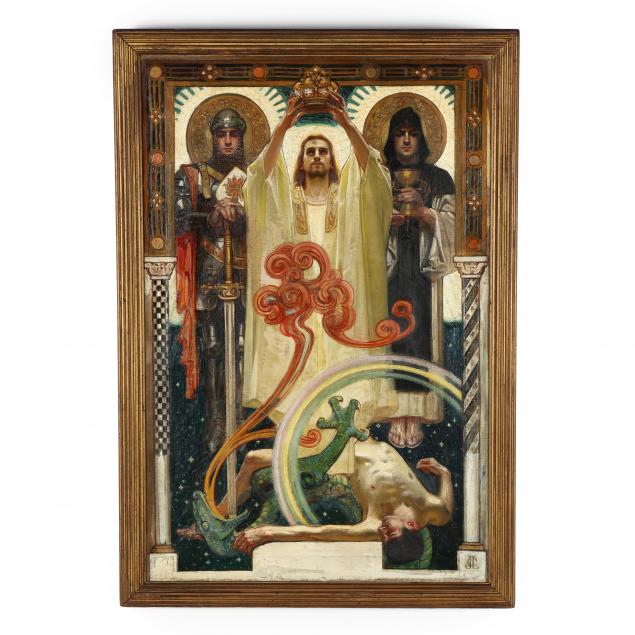

J.C. Leyendecker

Joseph Christian Leyendecker was one of the primary architects of the American ideal from which Charles Addams helped us to move on. As the most prolific illustration contributor to The Saturday Evening Post, Leyendecker literally showed America what it looked like in the first half of the 20th century. While Norman Rockwell is perhaps better known for his Saturday Evening Post covers, he followed solidly, unabashedly, in Leyendecker’s footsteps. It was Leyendecker who created the New Year’s baby, introduced the notion of fireworks on the 4th of July and of catching Mama kissing Santa Claus. He basically unzipped the American subconscious and inserted everything to which we would aspire for the next century or so, willingly or not.

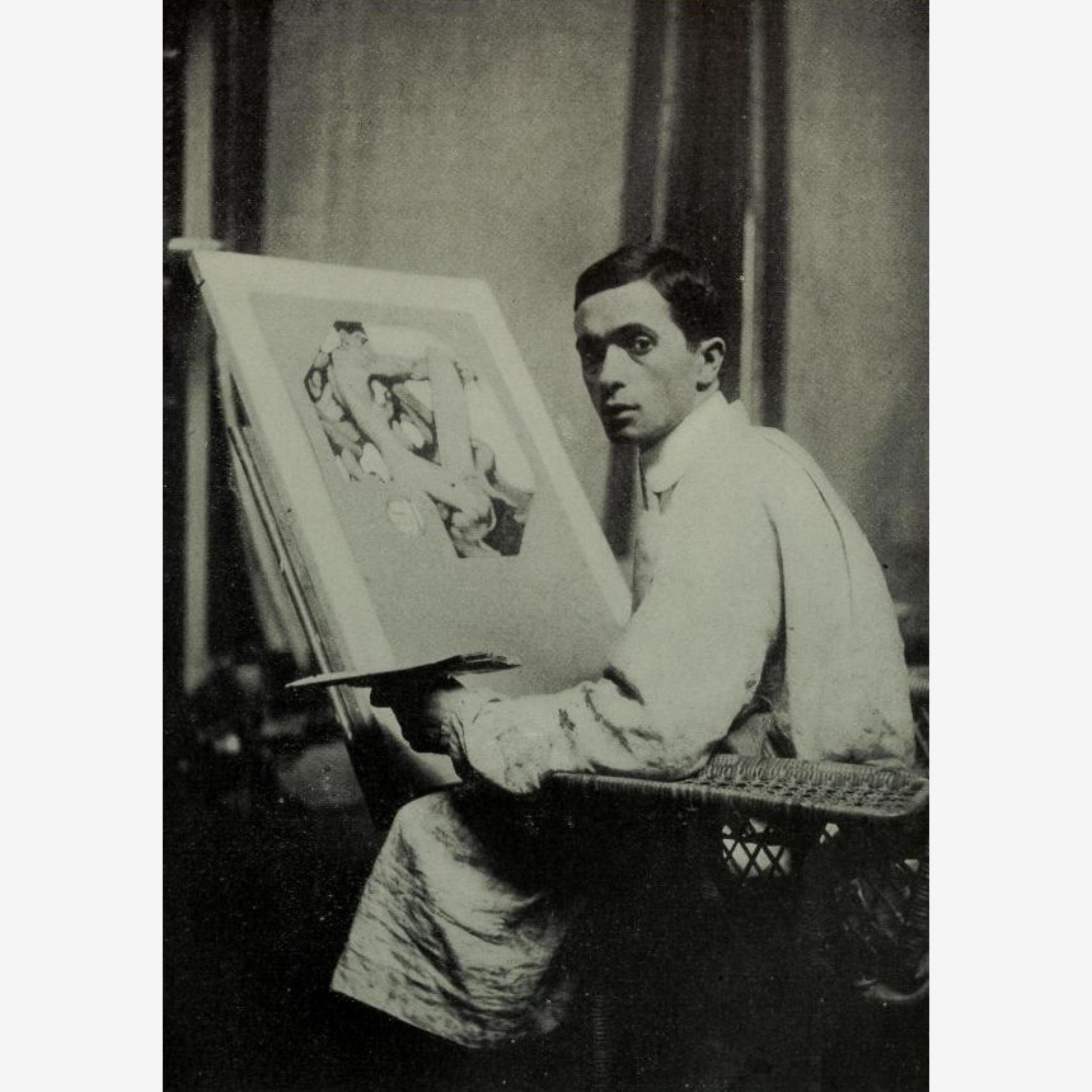

Leyendecker in his studio

Leyendecker was born in 1874 in Germany and immigrated to Chicago with his family in 1882 to be near his mother’s brother who had started the hugely successful McAvoy Brewing Company. Both J.C. and his younger brother Frank pursued art as a career - they attended the Art Institute of Chicago and the Académie Julian in Paris. When they returned to the United States, J.C. began taking advertising commissions for companies like Kuppenheimer clothing, Interwoven Socks, and Ivory Soap. He began working with The Saturday Evening Post in the early 1900s, and eventually made 322 total covers for the magazine.

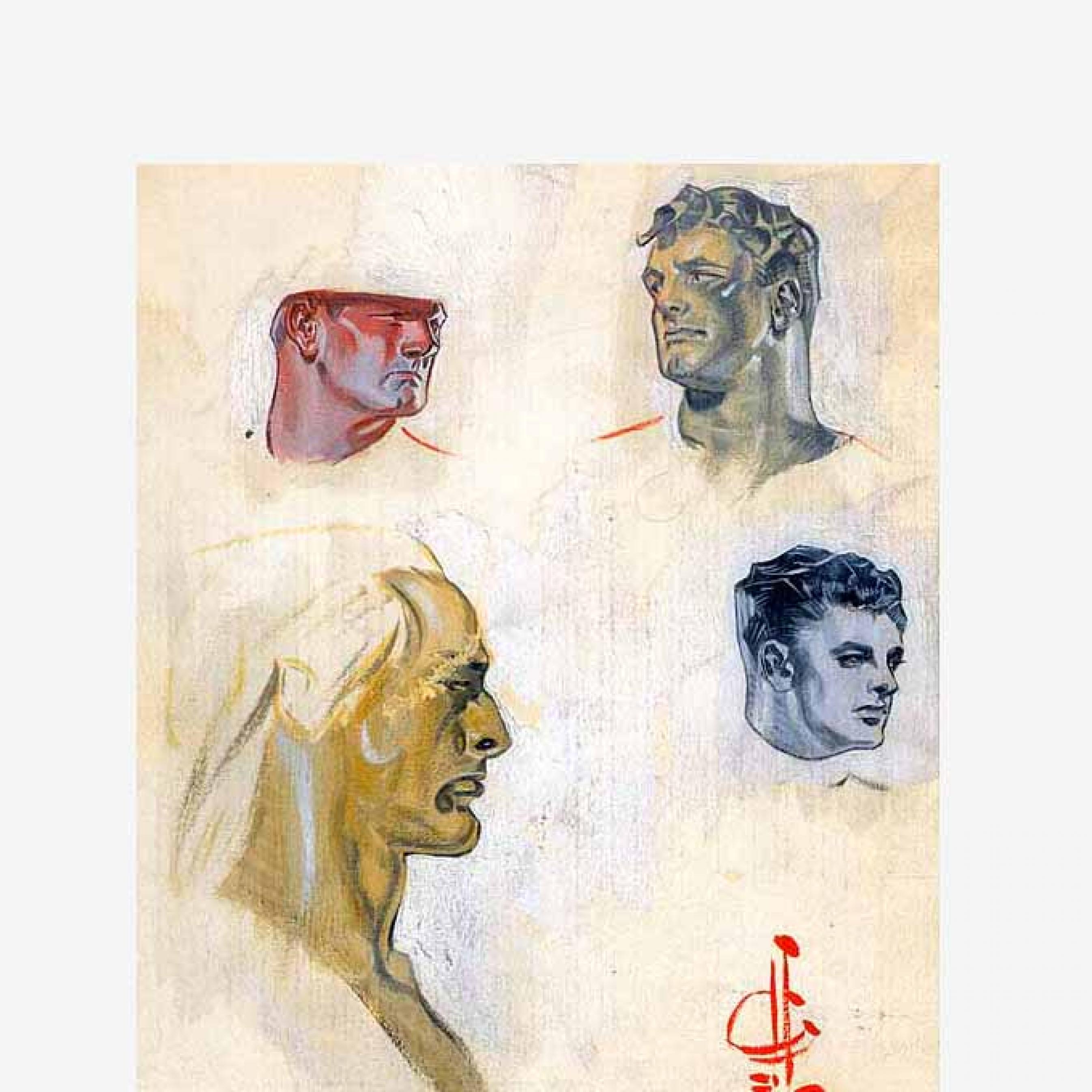

In 1914, Leyendecker, his sister Augusta, Frank, and Leyendecker’s personal secretary Charles Beach moved to the house in New Rochelle, New York where Leyendecker would live until he died. Beach lived with Leyendecker his entire adult life. Enter the elephant in the room. While it is of course futile to conjecture about the sexuality of someone long dead, it is perhaps equally useless to ignore the writing on the wall. And so we must take the facts of Leyendecker’s life for what they were: he and Beach lived together for nearly 50 years. Beach was Leyendecker’s model for a huge number of his illustrations. As the Arrow Collar Man, Beach became the ultimate depiction of the well-dressed man, often accompanied by one or two other well-dressed, or sometimes not-very-dressed, men. In one advertisement for government bonds, Leyendecker used Beach as the model for both a Boy Scout and Lady Liberty. Beach was Leyendecker’s muse, business and life partner.

After WWII, when photography took over as the primary mode of illustrating magazines, Leyendecker’s fortunes took a turn. Throughout the 20s and 30s, Leyendecker and Beach threw lavish parties at the New Rochelle house. But in the later years of his life, Leyendecker rarely had contact with anyone other than Beach and his sister. When he died in 1951, six people attended his funeral. Norman Rockwell was one of his pallbearers. Leyendecker left a small estate to Beach and his sister, who had to sell his vast catalogue of drawings in a yard sale on the front lawn of the New Rochelle house, for 75 cents a piece. It is only in recent decades that Leyendecker’s enormous influence on American culture has been unearthed and once again appreciated. And in the more accepting climate of the 21st century we are able to acknowledge him not only as an artist who visually defined “America” but one who did it while living how and with whom he pleased. As it turns out, Leyendecker drew the ideals of one generation and lived the ones of the future.

The Signature Spring Auction

Saturday, March 13th

9:00am (EST)

View Results

The Signature Spring Auction

Saturday, March 13th

9:00am (EST)

View Results