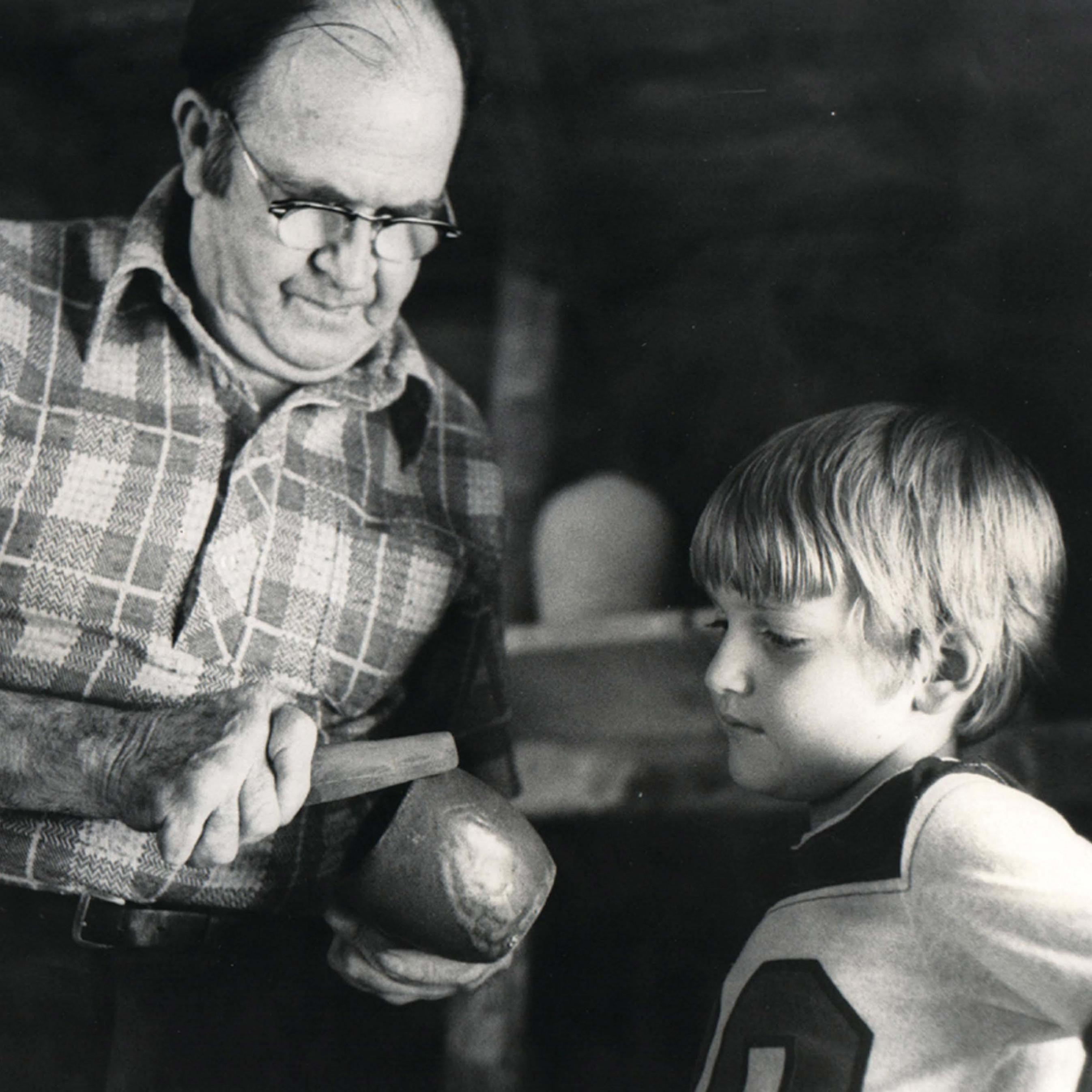

Ben Owen, Master Potter with his grandson, Ben Owen III. Photo by Mildred Allen, used with permission of Ben Owen Pottery.

Like Potter, Like Son

The history of North Carolina ceramics is one of generations of fathers passing down a utilitarian craft to their sons, who gradually turned it into an artform and a living. This Father's Day weekend, we look at how a few of the potters represented in The June Estate Auction maintained and grew their paternal legacy.

The Owens

Benjamin Wade Owen Sr., Master Potter (1904-1983), the first in the Owen family to make his living at ceramics, learned to work with clay from his father, Rufus Owen, who taught his three sons to make utilitarian vessels between farming chores. Ben Owen Sr. went on to work at Jugtown Pottery for over thirty years, and then opened his own shop in 1959, where he worked until he retired in 1972. When Owen's grandson, Ben III, was eight years old and could finally reach the wheel, he began daily afternoon pottery tutorials with his grandfather. In 1982, Ben II and Ben III re-opened Ben Sr.'s shop as Ben Owen Pottery. Ben Owen III continues to operate Ben Owen Pottery and lives in the house next to the studio with his family, which includes the fourth generation of Benjamin Wade Owens, Ben IV.

Ben Owen (NC) Master Potter Punch Bowl, in The June Estate Auction

Sid, Jason, and Matt Luck

The Lucks

Sid Luck is a fifth-generation potter. Luck's great-great grandfather William started the family tradition in the 1800s. At six years old, Sid's father James, who had been taught to throw pots by his own father, Bud, told him "you need to learn how to do this." And so he did. By thirteen, Luck was making small pieces for the Cole family pottery. But through the middle of the century, demand for North Carolina pottery wasn't high enough for Luck to branch out on his own, and so he continued to make pieces for the Coles on the side, while he taught science for 18 years to support himself.

But in the 1990s, as the rest of the country became enthusiastic about North Carolina ceramics, Luck finally gave up teaching to make pottery full time at his own shop, Luck's Wares. Luck trained his two sons, Matt and Jason, to make pottery as well. Jason is a patent attorney, and Matt owns a chicken farm, but both throw pots on the side, like their father did for so many years. At Luck's Wares, father and sons fire their pieces in a kiln built of bricks from the kilns of previous generations of Lucks, and use a wheel that belonged to Sid's father James.

The Hewitts

Unlike his pottery peers, contemporary ceramicist Mark Hewitt did not come from a long line of North Carolina potters. In fact, he did not come from North Carolina at all. Hewitt was born and raised in Stoke-on-Trent, England, near the Spode china factory. Hewitt's grandfather, Arthur Hewitt, took over as the director of Spode in the 1930s. Arthur Hewitt was responsible for major changes at Spode, most notably moving their production away from coal-burning kilns and into electrical and gas-powered kilns and other processes. Hewitt's son Gordon succeeded him at Spode, and it was expected that Mark would follow in their footsteps. But Mark was exposed to the world of studio pottery at university, and he decided to make that his focus rather than his father and grandfather's world of industrial pottery. Hewitt moved to Pittsboro, North Carolina in 1983, and set up his own studio. Since then the artisan with the English pottery roots has become a pillar in the North Carolina pottery community.

All three of these potters follow not only in their own fathers' footsteps, but in the tradition of North Carolina pottery in general, which is one long line of skills being passed down from generation to generation, hopefully far into the future.

The June Estate Auction

Thursday, June 24th

10:00am (EDT)

All three of these potters follow not only in their own fathers' footsteps, but in the tradition of North Carolina pottery in general, which is one long line of skills being passed down from generation to generation, hopefully far into the future.

The June Estate Auction

Thursday, June 24th

10:00am (EDT)