Living on the Live Edge

Whether in life or in craft, for George Nakashima the imperfections made all the difference.

Just as the knots, wormholes, and rough edges in the wood of Nakashima's iconic Modernist furniture are part of what make it so uniquely beautiful, the particularities of Nakashima's life formed the shape of his career and his legacy. As we look towards offering a Nakashima Walnut Double Dresser, being sold for the first time since it was purchased at the woodworker's shop in the 1960s, in our upcoming Modern Art & Design Auction, we explore the periods of Nakashima's life that left an indelible mark on his work.

The Ashram

The beginning of George Nakashima's career checked all the boxes for success: samurai ancestry, a Bachelor's degree in architecture from the University of Washington, a Master's degree (also in architecture) from MIT, even a year of study in Paris. But when his post-college employment went the way of the Great Depression, Nakashima did what all good highly educated Americans do in moments of job insecurity - he bought a steamship ticket around the world.

The Golconde Dormitory, Pondicherry, India

In 1934, Nakashima's travels found him in Japan, working for Antonin Raymond, the Czech American architect who collaborated with Frank Lloyd Wright on The Imperial Hotel in Tokyo. Nakashima worked for Raymond in Japan for a number of years, and in 1939, Raymond sent Nakashima to Pondicherry, India, to lead the construction of a Modernist dormitory for the Integral Yoga Ashram led by the famous yogi Sri Aurobindo.

Nakashima spent an extended period in Pondicherry building Golconde, as the dormitory was called. In addition to guiding its construction, he made furniture for the space, which was some of his very first furniture work. By the end of his time in India, Nakashima had become a member of the Ashram, and had been given the Sanskrit name Sundrananda, or "one who lives in beauty." Immersed in Integral Yoga, Nakashima embraced the practice's central belief that all things spend their physical lives in an evolution towards a pure spiritual existence. In later years, as Nakashima's woodworking and furniture-making style developed, his singularly deep relationship to his materials was directly influenced by Integral Yoga.

The interior of a room at Golconde, with furniture made by Nakashima

Nakashima said that "When trees mature, it is fair and moral that they are cut for man's use, as they would soon decay and return to the earth. Trees have a yearning to live again, perhaps to provide the beauty, strength and utility to serve man, even to become an object of great artistic worth." In an interview for Woodcraft magazine, Nakashima's daughter, Mira, said that Integral Yoga "reinforce[d] the possibility of divine inspiration and kept [his] ego under control, allowing the wood to speak for itself."

The Internment Camp

Nakashima returned to the United States in 1941, and decided to quit architecture in favor of making furniture. He set up a shop in the basement of a boys’ club in Seattle, teaching the young men woodworking in exchange for the use of their machinery. But in 1942, Nakashima, his wife Marion, and Mira, then an infant, were forced into an internment camp at Minidoka, Idaho, with 120,000 other Japanese-Americans.

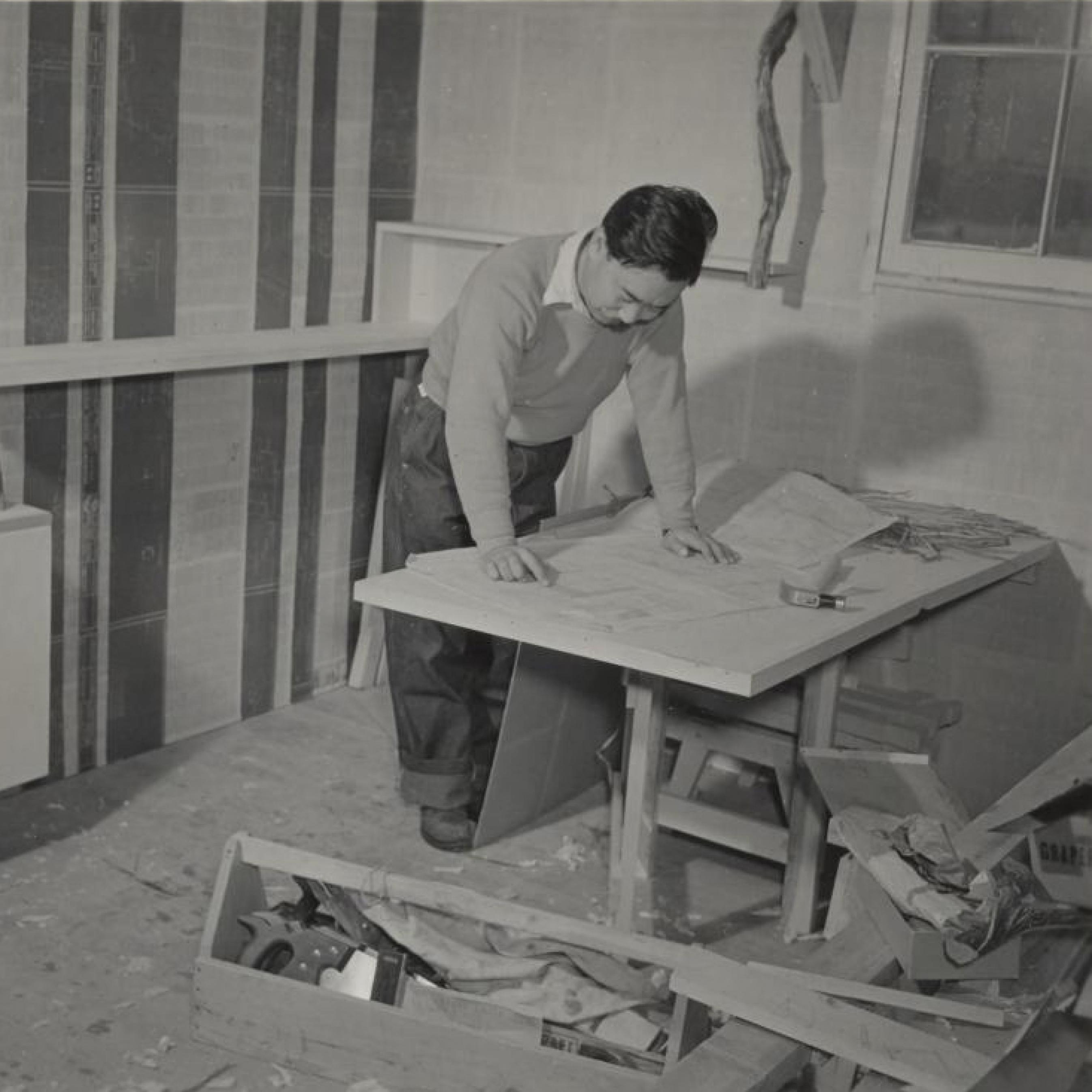

Nakashima at work at Minidoka

At Minidoka Nakashima met Gentaro Hikogawa, a master carpenter trained in Japan. Together, the two men went about making their camp barracks more livable. Limited to wood scraps from the camp’s construction, they built furniture from wood that normally would have been thrown out, full of wormholes and knots. Nakashima learned what would become his signature butterfly joint from Hikogawa, which they used to join smaller pieces of wood when they didn’t have one big enough to suit their purposes.

In 1943, Antonin Raymond had Nakashima and his family released from Minidoka by giving Nakashima work on his chicken farm in New Hope, PA. Nakashima wasn’t allowed to work with Raymond as an architect because the firm was working on government projects related to the war effort. Instead, he worked the farm. About his time as a farm laborer, Nakashima said "After a year of doing general farm work, it was quite clear to me that chickens and I were not compatible." And so again, Nakashima built furniture from found objects like old doors and lumber scraps. When the Nakashimas were finally released from Raymond’s protective custody in 1945, Nakashima went back to work for himself. With no money, he would go to the lumber yard and get the cheapest pieces he could, often “off-cuts” from quarter sawn boards.

At first, the methods Nakashima developed for highlighting the flaws in the wood in his pieces were off-putting to buyers. But as his work gained a following, the way that Nakashima created beauty from imperfection brought a premium. The butterfly joint became a defining feature of his work, and the “live edge” of unfinished boards evolved into style of its own that has inspired untold numbers of followers.

Life presented George Nakashima with both opportunities and challenges, and he found a way to channel them all into his striking designs. Just like the wood he saved from the scrap pile, no experience in Nakashima's life was wasted. Instead, detours and bends in the road simply became part of his beautiful path.

Below, works by Nakashima from our previous auctions.

Modern Art & Design

Thursday, August 19th

10:00am (EDT)

At first, the methods Nakashima developed for highlighting the flaws in the wood in his pieces were off-putting to buyers. But as his work gained a following, the way that Nakashima created beauty from imperfection brought a premium. The butterfly joint became a defining feature of his work, and the “live edge” of unfinished boards evolved into style of its own that has inspired untold numbers of followers.

Life presented George Nakashima with both opportunities and challenges, and he found a way to channel them all into his striking designs. Just like the wood he saved from the scrap pile, no experience in Nakashima's life was wasted. Instead, detours and bends in the road simply became part of his beautiful path.

Below, works by Nakashima from our previous auctions.

Modern Art & Design

Thursday, August 19th

10:00am (EDT)