Scotch & Climate Change

One look at any of the scotch distilleries perched picturesquely on the shores of Islay serves as a reminder of their exposure to the elements. The relentless environment in which scotch is made has long been part of its charm, but with climate change intensifying, environmental concerns are quickly becoming production hurdles.

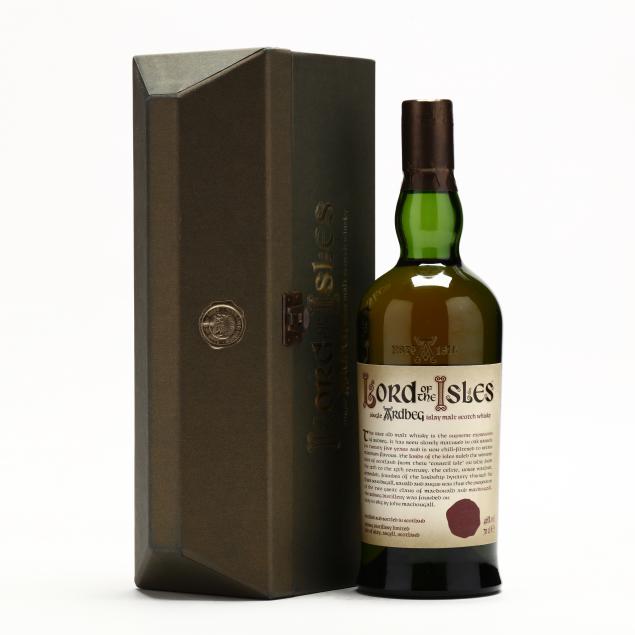

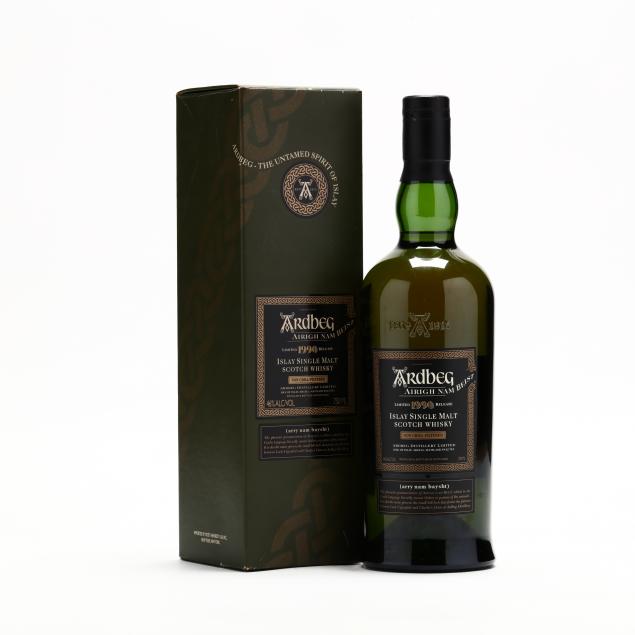

Among the many bottles of storied scotch whisky in our recent Rare Spirits Auction was a very strong showing from some of the most famous distilleries on the Scottish Isle of Islay in the Southern Inner Hebrides - Bowmore, Laphroaig, Lagavulin, Ardbeg, and the ghost distillery Port Ellen. Bowmore, the oldest licensed distillery on the island, has been making scotch there since 1779. But the world has changed since the eighteenth century, and the distilling traditions that ground the scotch industry may have to change with it. Read on to find out which aspects of the scotch distilling process are affected by climate change, and what the scotch industry is doing about it.

Peat

We may have the scotch industry to thank for putting peat on our radar - in what context other than the smoky aroma of your whisky does the partially decomposed mash of wet, dead vegetation come up in regular conversation? But while Scottish peat has the glamorous job of flavoring drying grain, peat the world over (and there are peatlands on every continent) has the very important job of…..existing.

Because peat is essentially the arrested state of thousands of years of rotting vegetation, it holds captive all the carbon that the decomposition process would otherwise release into the atmosphere. Which is great, until we start digging it up for fuel, or to get it out of the way for land development, at which point all of that carbon is let loose to wreak its havoc. The carbon released from the peat that is extracted in the United Kingdom every year is equal to that of the annual greenhouse gas emissions of roughly twelve million cars.

Scottish peat "stooks"

Scots of yore, gathering peat

Of course, the Scots of yore who burned peat to dry the malted barley for their scotch, giving the whisky its distinctive flavor, did not know about greenhouse gases. In the case of Islay whiskies, local peat is given credit for some of the briny, seaside character of the spirit. And though distilleries no longer use peat as their primary fuel for drying grain, they do burn smaller amounts of it to impart that unmistakable smokiness. Peat is an irreplaceable part of the scotch process.

And 80% of the United Kingdom’s peatlands have been compromised, though mostly for horticultural and fuel uses, not for scotch production. But even though distillers account for only 1% of Scotland’s peat extraction, they are perhaps peat’s highest profile consumer, and therefore one of the best advocates for the protection of peatlands.

With that knowledge in their pockets, some scotch makers are doing their part to preserve the natural resource. Diageo, the global spirits company that owns Lagavulin, started a 700 acre peat restoration project. Other scotch producers are proposing using peat that has already been removed for purposes other than whisky-making, though that would require surrendering the site-specific character of the local peat. And the Scotch Whisky Association has since 2009 been working on and updating a sustainability initiative that addresses peat conservation. They recognize their vital role, along with funding restoration projects, as the industry that can most readily bring global awareness to the plight of peatlands worldwide.

With that knowledge in their pockets, some scotch makers are doing their part to preserve the natural resource. Diageo, the global spirits company that owns Lagavulin, started a 700 acre peat restoration project. Other scotch producers are proposing using peat that has already been removed for purposes other than whisky-making, though that would require surrendering the site-specific character of the local peat. And the Scotch Whisky Association has since 2009 been working on and updating a sustainability initiative that addresses peat conservation. They recognize their vital role, along with funding restoration projects, as the industry that can most readily bring global awareness to the plight of peatlands worldwide.

Water

Water, water everywhere…..and lots of scotch to drink. For now, at least. Scotland, like every other island nation, is acutely aware of their proximity to the water these days. As scientists track the melting of polar ice caps and project the rise of sea levels, coastal establishments everywhere are bracing for impact. And Islay’s distilleries are as coastal as they can get. When the distilleries were established, they were built RIGHT on the water, because at that time, boats were the most efficient means of transporting grain and finished spirits on and off the island.

A scene from “Lines (57° 59’N, 7° 16’W)”

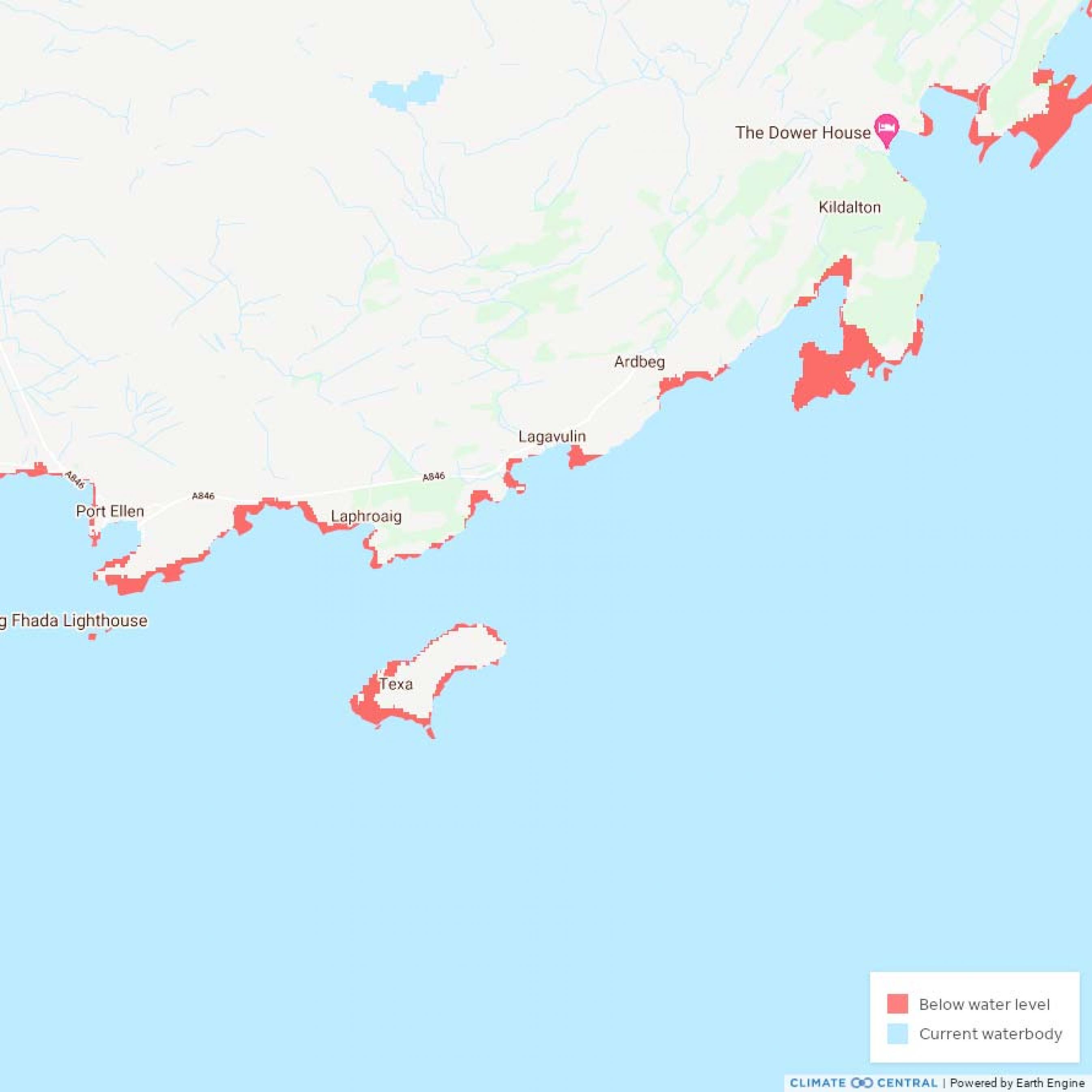

Now, however, that extreme proximity to the water may become a liability. In recent years, the Scottish Environment Protection Agency published an interactive map that shows which parts of the Scottish islands will be underwater by 2050 if nothing is done to slow climate change. Some parts of Scotland face nearly inevitable submersion. A 2019 art installation on the Isle of Uist, in the Outer Hebrides, illustrated how dramatic the change of the sea level will be. Called “Lines (57° 59’N, 7° 16’W)”, and designed by Finnish artists Pekka Niittyvirta and Timo Aho, the installation placed lines of LED lights on structures near the shoreline to show how high the water will eventually rise.

Detail of the SEPA map of water level rise in 2050

While the Inner Southern Hebrides will fare better than the Outer Hebrides, the fact that the Islay distilleries lie as close to the water as physically possible means that any sea level rise will increase their risk of flooding, particularly given the increased risk of strong storms due to global warming.

Ironically, global warming also puts scotch distilleries at risk of running out of fresh water, which they need at several steps throughout the distillation process. During a 2007 drought, several distilleries had to halt operations all together, and others were faced with bringing water in by tanker. Responsible water usage is another area that the Scotch Whisky Association’s climate initiatives address, much in the same twofold way they do peat harvesting. The SWA sees the need for scotch producers to both reduce their water usage and become stewards of the various freshwater sources on which they are so dependent.

Like any other product of the land on which it is made, scotch whisky is caught in the crosshairs of climate change. And, like any other product that gets part of its value from centuries of traditional production, the method of scotch’s making can’t turn on a dime. The scotch whisky industry is left to innovate in a particularly challenging fashion - change the effects of their production without changing the essence of their methods or their product. What can single malt enthusiasts do to help? Buy old scotch, of course. We’ve got just the bottle for you.

Rare Spirits

Friday, September 17th

12:00pm (EDT)

Featured Islay Whiskies

Like any other product of the land on which it is made, scotch whisky is caught in the crosshairs of climate change. And, like any other product that gets part of its value from centuries of traditional production, the method of scotch’s making can’t turn on a dime. The scotch whisky industry is left to innovate in a particularly challenging fashion - change the effects of their production without changing the essence of their methods or their product. What can single malt enthusiasts do to help? Buy old scotch, of course. We’ve got just the bottle for you.

Rare Spirits

Friday, September 17th

12:00pm (EDT)

Featured Islay Whiskies