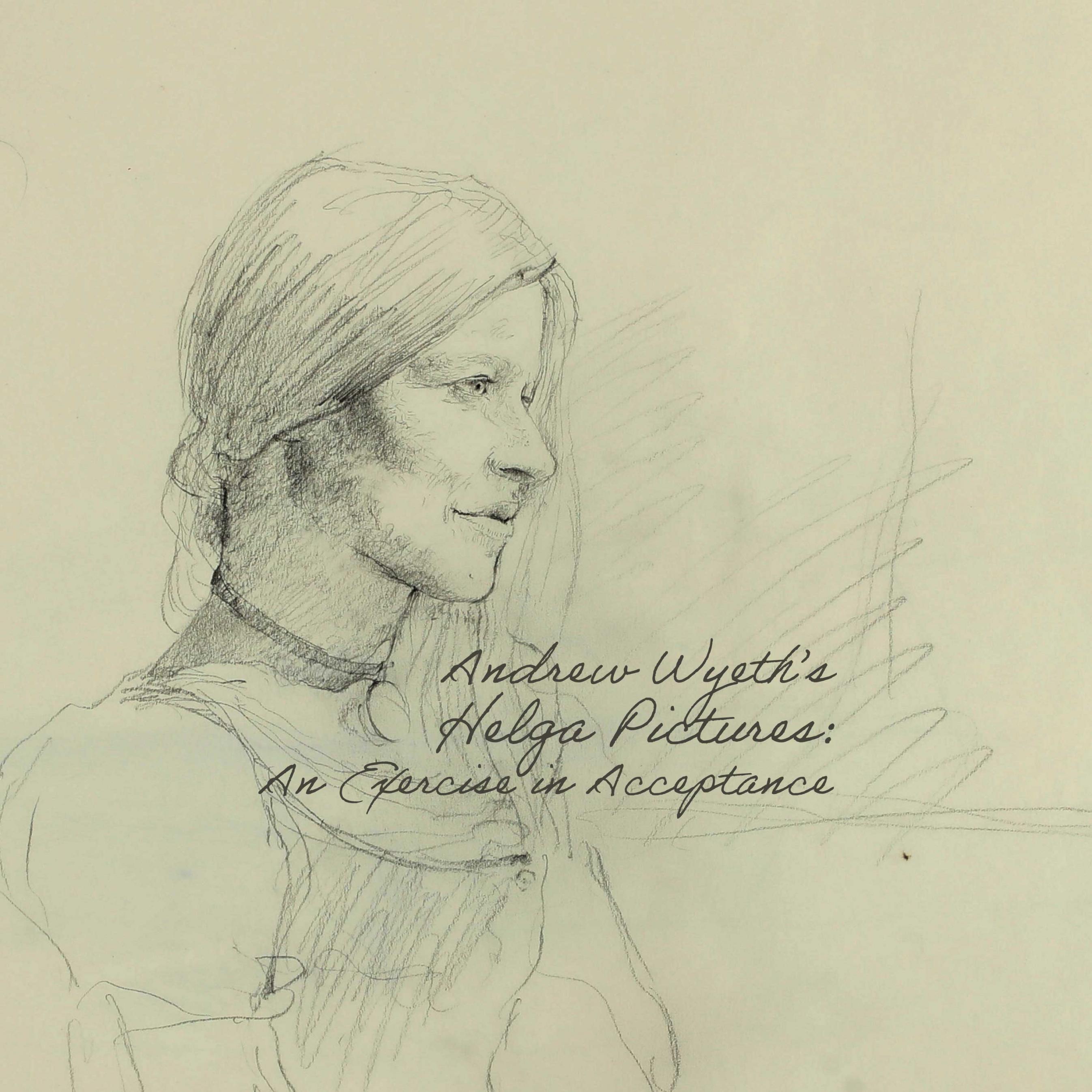

Here is what we know: through the 1970’s and early 1980’s, Andrew Wyeth created over 240 works of art centered around Helga Testorf, a German immigrant domestic employee who liked to wear her hair in two long blonde braids. Here is what we don’t know: anything else. But if a dive into the voluminous commentary about Andrew Wyeth’s Helga pictures will tell you one thing, it’s that not knowing is very, very hard for us to accept.

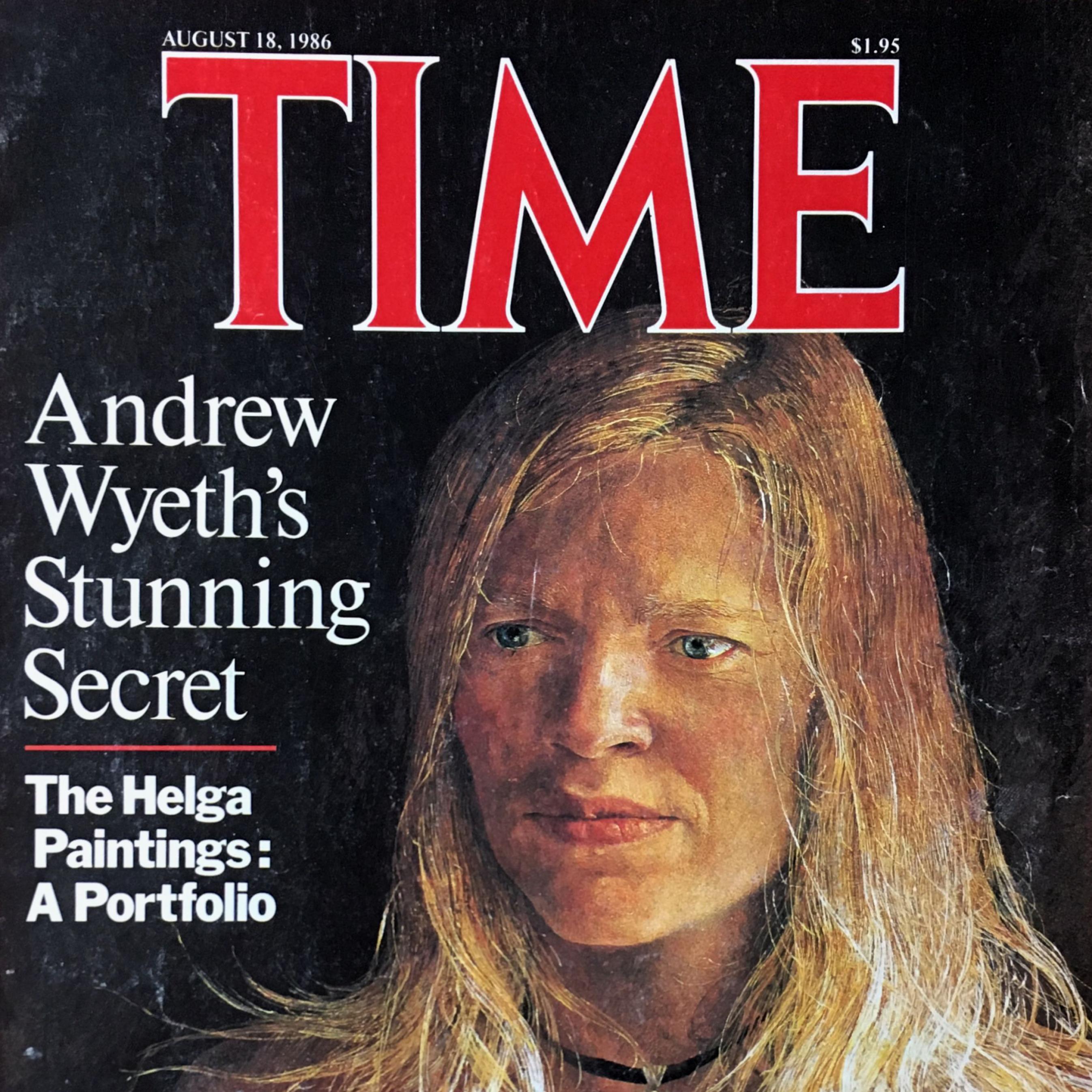

In mid-August of 1986, American news outlets exploded with the story of an enormous cache of paintings by Andrew Wyeth that up to that moment he had hidden from the whole world, including, most titillatingly, his wife, given the fact that all the works were of one woman (not his wife) and in many of them she wasn’t wearing clothes. The media blitz was quick and thorough - Time magazine and Newsweek put the revelation of the Helga paintings on their covers. The New York Times ran interviews with Wyeth’s wife, Betsy. Connie Chung announced it all on the evening news. The world was shocked, and loved every minute of it.

In the aftermath of this media maelstrom, the art world and the American public collectively tied itself into knots for years, trying to come to rest with some conclusion about the Helga paintings. Conspiracy theories flourished - journalists pointed out that both the Wyeths and the wealthy businessman, Leonard E.B. Andrews, who bought the complete Helga series and its reproduction rights, enjoyed hefty financial gains fueled, undeniably, by the public fascination with being let in on what looked like a very private relationship. Surely that meant that the whole thing had been a publicity stunt? Establishment art critics, who have always had a testy relationship with Andrew Wyeth’s work, rushed to declare their skepticism about the Wyeths’ story of the Helga paintings. They cried from the rooftops of major publications that they had not been taken in by the drama, and pointed out that they had not been the ones who wrote up the story in those first summer weeks of flushed excitement over the Helga pictures. This skepticism carries a strong whiff of jealousy. The critical world has never been kind to artists who dare to make money while they’re still alive - clearly commercial success must somehow negate the legitimacy of the art.

At the heart of all this hand-wringing are some very simple, itchily familiar questions. Was it an affair? Did the wife know? If she knew, why did she stay? We don’t like to admit that we want these answers, particularly when it comes to art. It’s ART, surely our interest in it can’t be so prurient. For their part, the Wyeths and Helga herself stayed obligingly oblique on the matter, allowing us to keep a heady theoretical distance from our own sordid curiosity. Yes, Betsy answered questions, but one minute she was famously declaring that the Helga pictures were obviously about “love” and the next she was telling the NY Times that sex couldn’t possibly have been part of the relationship because “‘If there is this sexual thing,’ she said, ‘if he went over the bounds it wouldn't be a painting. He would lose the magic. It would go.’”Helga was also interviewed several times about her relationship with Wyeth. Each time the interview was sold to us as Helga finally breaking her long silence. But when she spoke up she said things like “There are many different ways to make love” and “Andy said our life was something that we dreamed about - he said I don’t even want to talk about it, I’m afraid it disappears...the spirit is all around us, you just have to be ready to pick it up.” Lovely, but hardly a concrete accounting of what happened between them. And Andrew Wyeth himself spoke all the time of love in relationship to his art - according to him, love was at the root of all his pictures, whether they be of a winter field, a dog by a fireplace, or a naked woman.

One way that critics have dealt with all this not-knowing is to declare that they will ignore the dramatic backstory, put on their mental blinders, and assess the art solely on its own technical merits. But this effort is akin to a jury trying to unhear whatever has caused a courtroom objection. Once you know the story, you can’t unknow it. And so we must come back to the facts.

One way that critics have dealt with all this not-knowing is to declare that they will ignore the dramatic backstory, put on their mental blinders, and assess the art solely on its own technical merits. But this effort is akin to a jury trying to unhear whatever has caused a courtroom objection. Once you know the story, you can’t unknow it. And so we must come back to the facts.

Betsy and Andrew Wyeth married when Betsy was 19 years old, and she immediately and successfully took over the business side of his career - a bracing accomplishment for a young woman in mid-century America. Betsy is one of those strong women who paved the way for all of the ambitious girls who came after her. The Wyeths were married for over 70 years. Helga, far from dissolving into the shadows, was Andrew’s studio assistant until late into his life, and eventually his caretaker and companion. These three people found their own angle of repose - and seemed comfortable letting the rest of us wrestle with not knowing how they did it. Whether it was contentious or amicable, secretive or open, planned or spontaneous, the nature of their artistic and personal arrangement was always ultimately none of our business.

So now, as we look at the Helga pictures, all of this opacity is necessarily part of the experience. But one thing we can see is that we must accept and move on. The Wyeths and Helga did it, perhaps we can too.

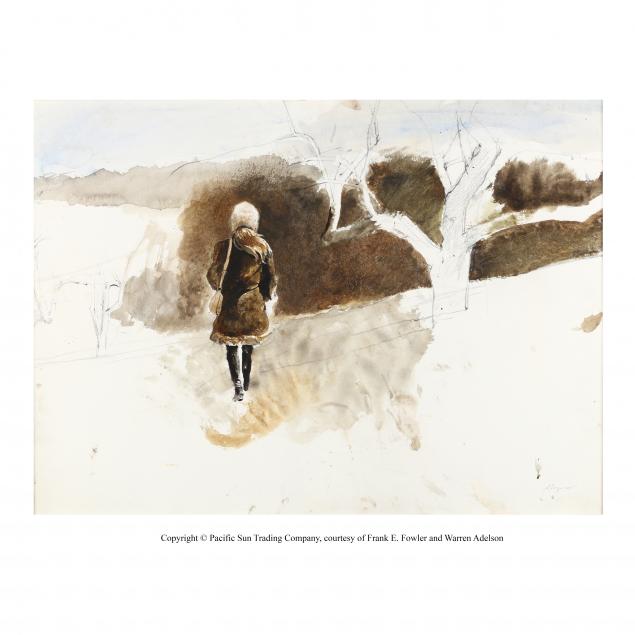

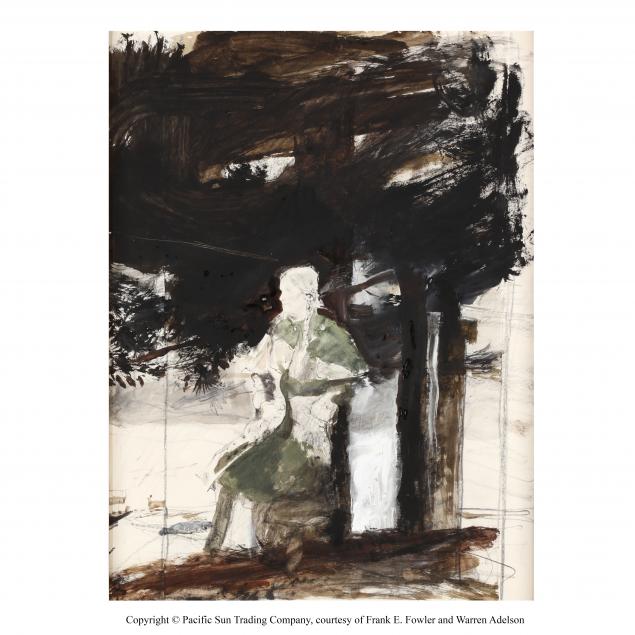

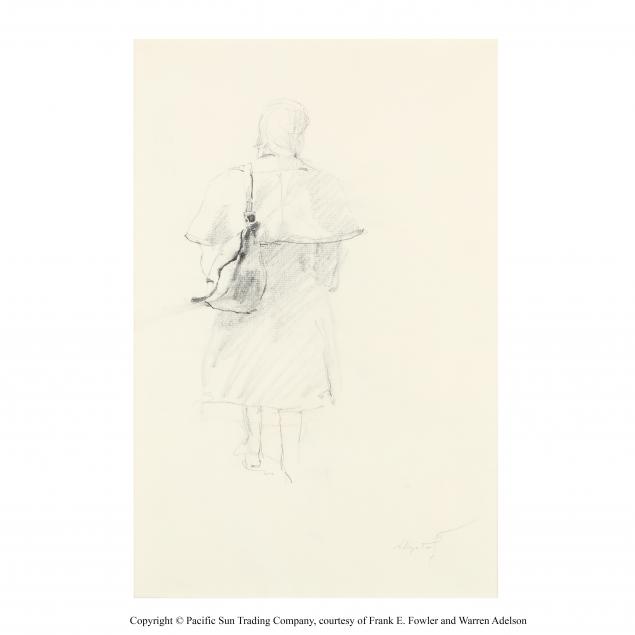

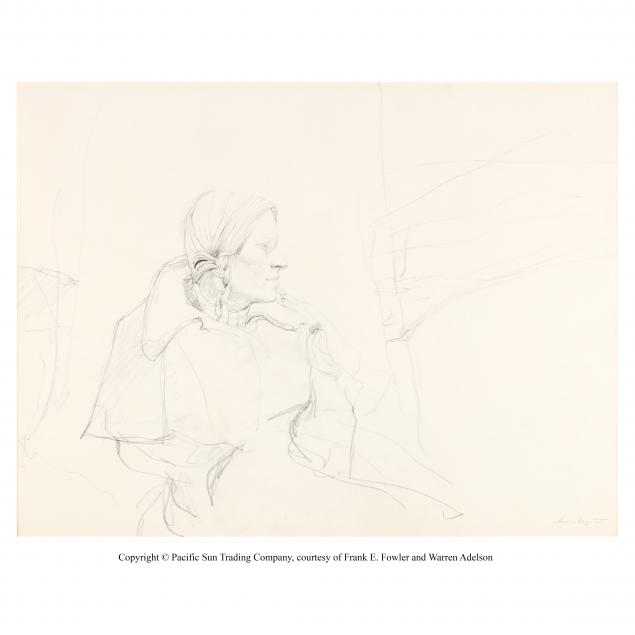

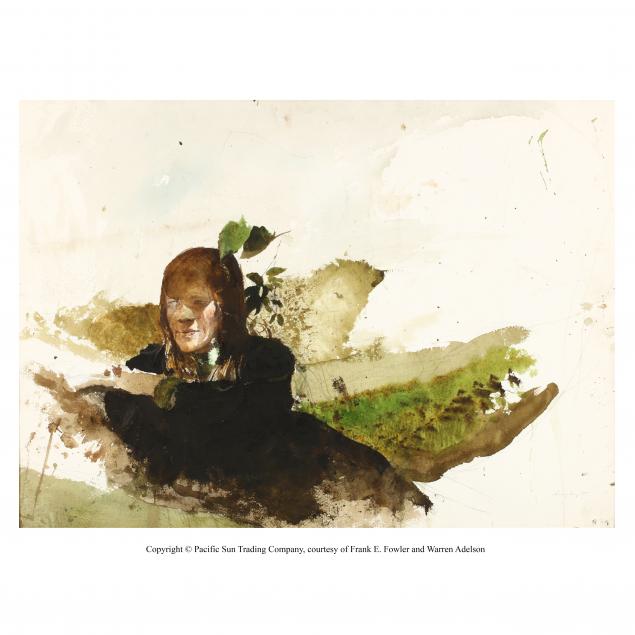

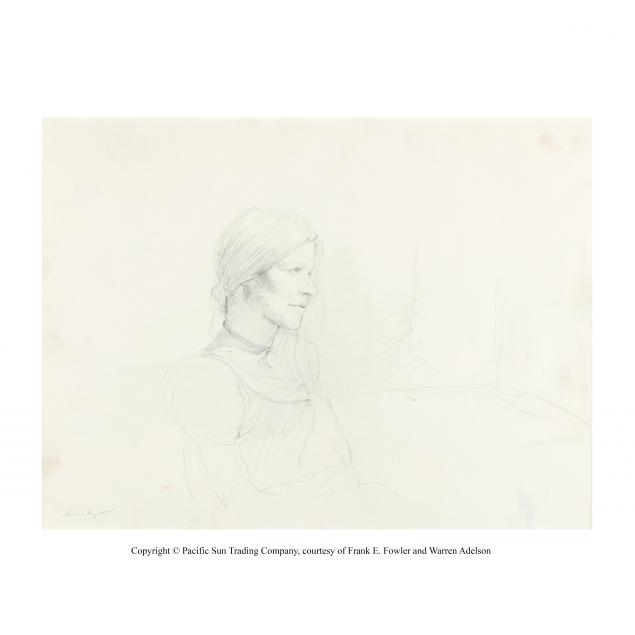

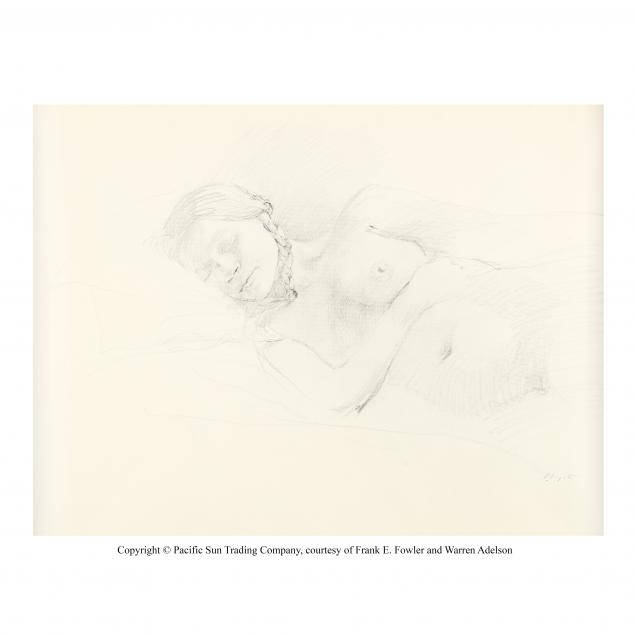

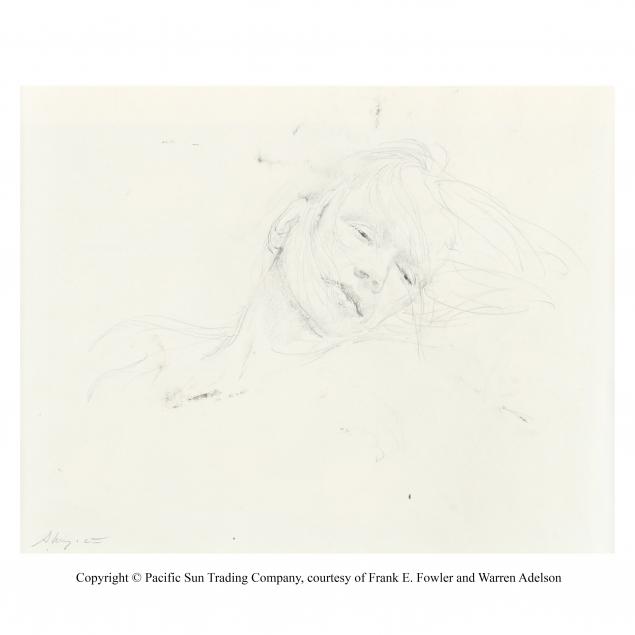

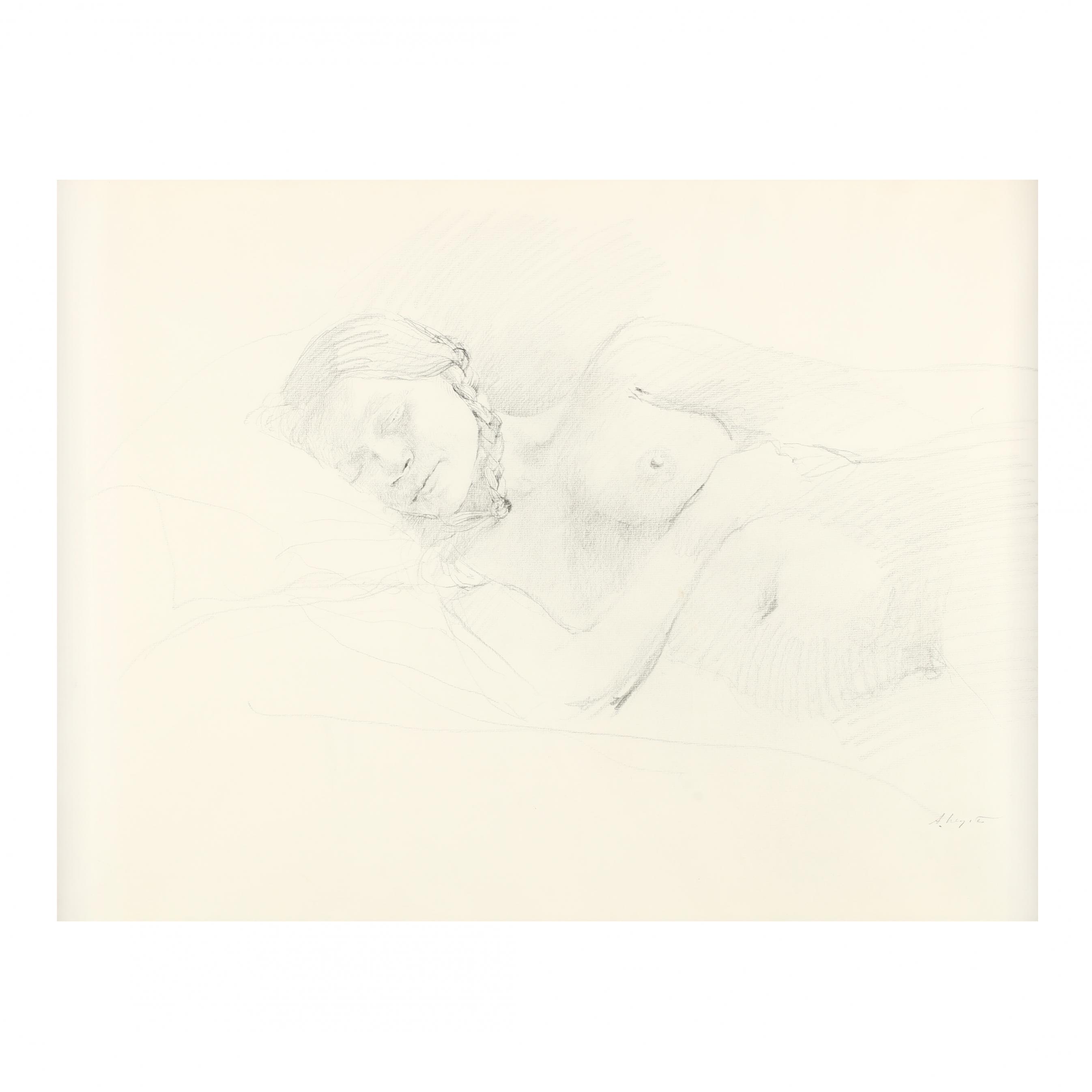

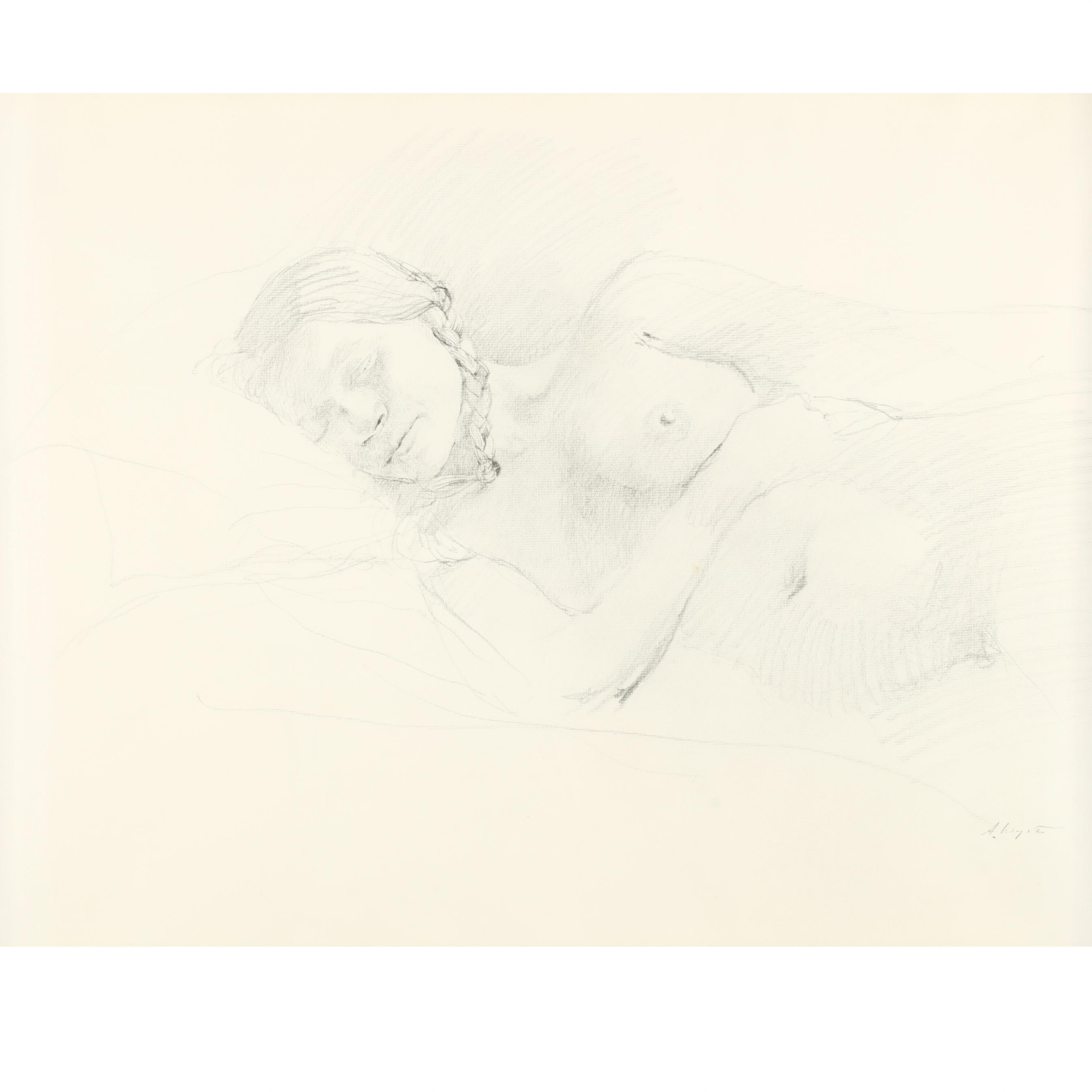

The works from the Helga paintings being offered in our December 6th auction of a Single-Owner Collection are below. View the full catalogue for the auction, including several more works by Andrew Wyeth, here.

The works from the Helga paintings being offered in our December 6th auction of a Single-Owner Collection are below. View the full catalogue for the auction, including several more works by Andrew Wyeth, here.