The Traditional Iconoclast: Artist Toko Shinoda

With her groundbreakingly simple sumi-e works and lithographs, Toko Shinoda, who passed away this March just three weeks shy of her 108th birthday, used classic technique to create revolutionary Japanese art.

Shinoda, who studied calligraphy and classic literature from the age of six, wore the traditional Japanese kimono her entire life. But, unlike other women, who wore their obi belts high up on their waists, Shinoda always wore hers low, just on top of her hips, like a man. This sartorial detail perhaps encapsulates everything there is to know about Shinoda: she had deep respect for her cultural heritage, but she never changed herself to accommodate it. She took tradition on her own terms.

Born in 1913, Shinoda was the fifth of seven children. She began her calligraphy classes at the insistence of her father, who, while he was a great lover of Japanese poetry and could be strict, had a touch of the nonconformist in him as well. He rode one of the first three bicycles ever imported to Japan, and, by educating his daughter, gave her a path to independence that was not often afforded Japanese women in the early 20th century.

By the time she was in her teens, Shinoda knew she wanted to make art her life’s work, and also that the confines of traditional calligraphy couldn’t satisfy her creative impulse. In an interview from the 1980s she described feeling intense jealousy of the original creators of the calligraphic strokes - she, too, wanted to create something expressive of her very own, rather than forever copying the ancient work of others.

Born in 1913, Shinoda was the fifth of seven children. She began her calligraphy classes at the insistence of her father, who, while he was a great lover of Japanese poetry and could be strict, had a touch of the nonconformist in him as well. He rode one of the first three bicycles ever imported to Japan, and, by educating his daughter, gave her a path to independence that was not often afforded Japanese women in the early 20th century.

By the time she was in her teens, Shinoda knew she wanted to make art her life’s work, and also that the confines of traditional calligraphy couldn’t satisfy her creative impulse. In an interview from the 1980s she described feeling intense jealousy of the original creators of the calligraphic strokes - she, too, wanted to create something expressive of her very own, rather than forever copying the ancient work of others.

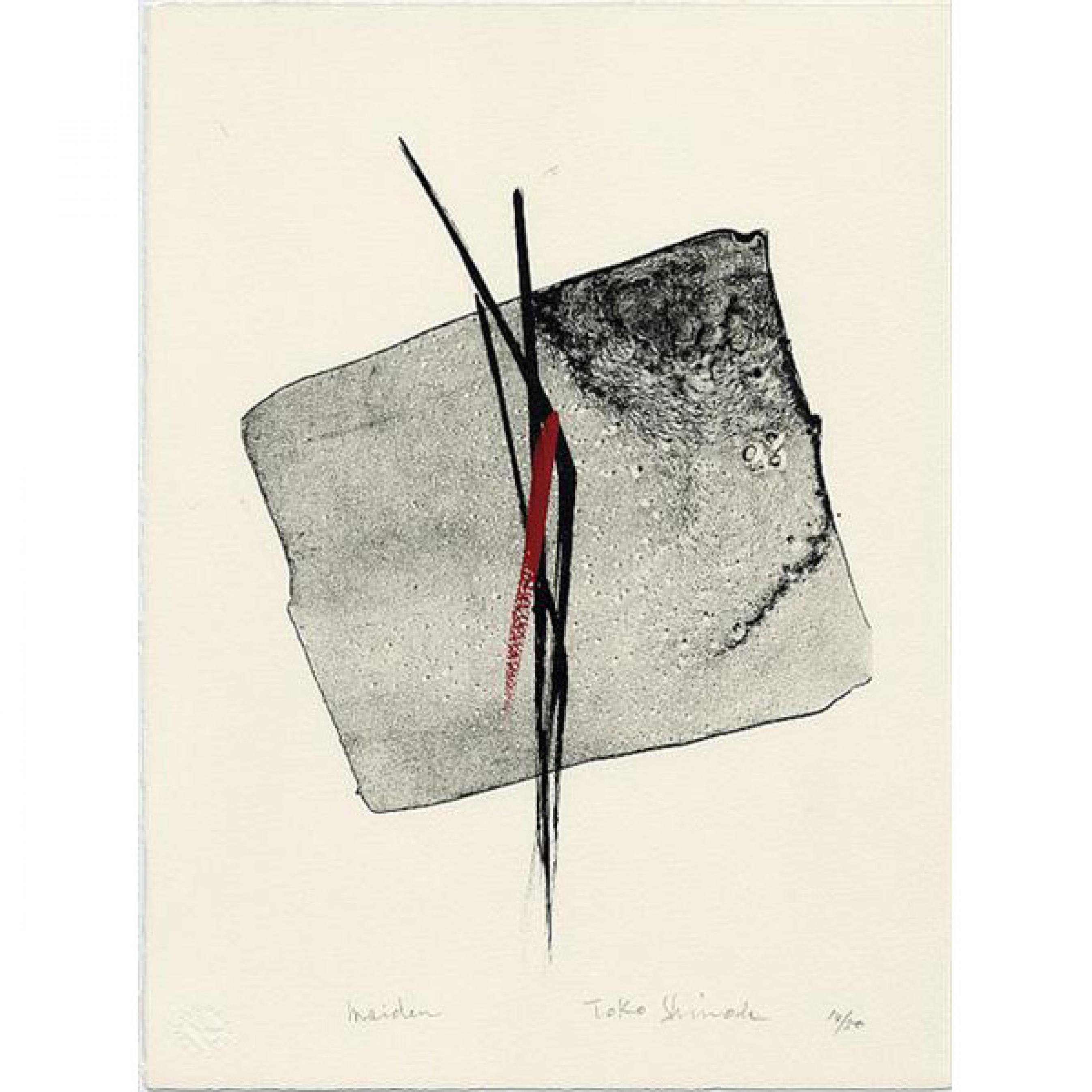

Toko Shinoda, Maiden

She began to add strokes to the symbols for things like “water” and “river” to create a form that, to her mind, more accurately represented the spirit of the thing. Her teachers didn’t take kindly to the embellishments. Later in life, when Shinoda worked purely in abstracts, she would often add vermilion streaks to her pieces in homage to the red correction marks her calligraphy teachers made to her schoolwork.

In the 1950s, as the post-war art scene across the globe reshaped itself in the image of the new world order, Shinoda found herself drawn to the United States. Her United States gallerist, Allison Tolman, of the Tolman Collection, said that Shinoda felt that everything interesting was happening in the US. As a young, unmarried, Japanese woman, it wasn’t easy for her to travel to the United States, but through a family friend she was able to obtain a three month tourist visa, which she then extended time after time until she had stayed for two years. While in the US, Shinoda spent substantial time with the stars of the abstract expressionist movement, such as Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, Helen Frankenthaler, and others. She was taken on by the gallerist Betty Parsons, who also represented many of these famous American artists. Tolman, whose father’s gallery in Tokyo worked with Shinoda for decades, suspects that this overseas success helped cement Shinoda’s credibility as an artist when she returned home to Japan in 1958.

Toko Shinoda, Rivage

Shinoda’s artistic legacy is often described as the application of abstract expressionism to the medium of sumi-e ink. But she herself did not see it that way. To her, the decades of training she received in traditional Japanese technique far outweighed the several years' influence of western style. She used literally centuries-old sumi (ink) sticks to make her art. So while she turned to abstraction to express ineffable concepts in her artwork, she resisted categorization her entire life.

As Tolman notes, Shinoda’s independence was her defining feature. Tolman met Shinoda when she (Tolman) was just a young girl, and she was drawn to the artist’s unique autonomy, so unusual in Japanese women of her generation. Tolman recalls one instance in which she was interpreting for Shinoda with a reporter covering one of her exhibits. Shinoda thought the reporter’s questions revealed a lack of familiarity with her work. She demanded that Tolman tell the reporter that he should go see her work before he asked her questions about it. Tolman demurred in the interest of public relations; Shinoda insisted. When Tolman finally gently told the reporter that Shinoda suggested he might find the answers to some of his questions in the actual artwork, he replied “I don’t think that’s all she said.”

Allison Tolman and Toko Shinoda, sharing a laugh. Photo courtesy of Kiyoyuki Fukuda, the Tolman Collection of Tokyo.

The artwork we offered in our Signature Fall Auction was a lithograph entitled Spiritual. Shinoda began making prints in the 1960s after a prominent printmaker, Arthur Flory, suggested it suited her style. She worked her entire career with master printmaker Kihachi Kimura. She found their collaboration to be essential to the making of successful art. In her own 1983 book, Sono hi no sumi, she wrote that lithography “is where you can contain the work of the living (moving) brush and entrust a ‘prayerful spirit’ to the person who brings it back to life. That spirit generates an interaction between artist and printer, and I always enjoy the ‘electric’ current bouncing back and forth between us as I work on a lithograph.” In every instance where color is present in one of her lithographs, such as the blue swath in Spiritual, it was applied by hand by Shinoda herself, after Kimura had printed the black hues, effectively rendering every one of the edition an original. When Kimura retired in 2007, Shinoda simply stopped making prints.

For all her independence and scholarliness, Tolman says Shinoda was far from monk-ish. Though she didn’t have children of her own, she was essentially the matriarch of a large family of nieces, nephews, and their children. She could just as easily discuss baseball as she could 14th century Japanese poetry (which sometimes made cameos in her artwork). When she painted, she liked to listen to Western classical music and jazz. In a culture and an era that prized conformity, Toko Shinoda blazed her own trail, personally, professionally, and creatively, for over a century.

Photo courtesy of Kiyoyuki Fukuda, the Tolman Collection of Tokyo